As we make management decisions to survive what looks to be a severe drought, I can’t help but think how right Mark Twain was so many years ago.

Most reservoirs are low this year as we head into the growing season. When I talk to producers and discuss their water allocations and hear 11% and 22%, I begin to cringe. Those that have supplemental wells for surface irrigation might not suffer as much, but then look at the soil moisture in the ground and tie it to how those rangelands are doing.

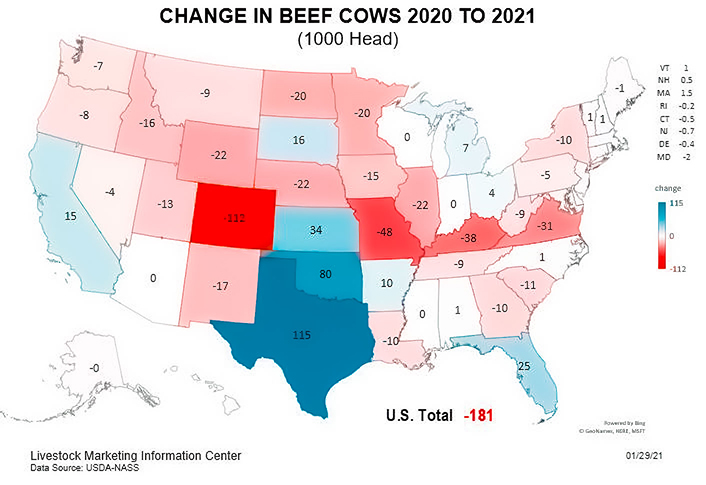

I just listened to an agricultural economic update from Washington State University this morning learning about exports and shipping situations; cattle inventories in the West; price volatility; and more about drought. The temperatures are expected to be above normal and our precipitation is expected to be below normal throughout most of the west. I see that D4 dark red inching its way up the State of Nevada each week in the US Drought Monitor.

I know all too well what this means as we have been here before, and we will be here again. It takes me back to when I was a newspaper reporter right out of college covering the Walker River Basin water issues and in my first month on the job I had a county commissioner and the water district manager in a fist fight on the library lawn. While it might not be fists and face-to-face directness anymore, it is a new technological advanced way of doing business. Who has the water right? Who needs the water right? Who is using the water right?

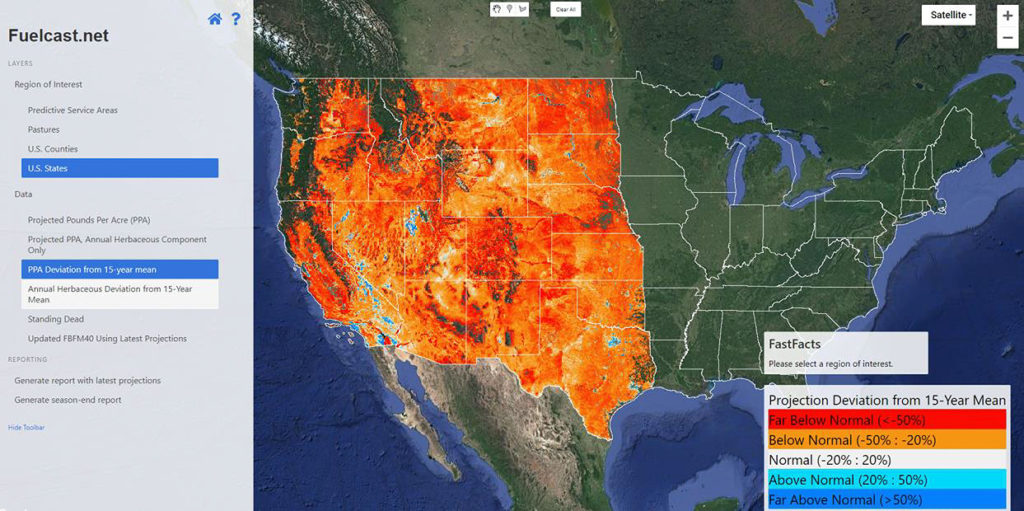

The water topics that were put on the back burner are reemerging. Part of the presentation this morning was the remote sensing of the vegetation (fuels) on the rangeland and they used a map of the Western US to discuss possible cattle liquidations due to drought. I am by no means a remote sensing expert and the thought of remote sensing intrigues me, but my first question is the overall impact of this new technology. Is this going to be used to determine AUMs and manage range units? How is the data being used? The website is fuelcast.net and was designed for rangeland managers, fire specialists, and producers.

We see these issues in the US Drought Monitor that were originally created in 1999. The Drought Monitor was not originally created to trigger USDA Programs like it does today. The US Drought monitor currently designates drought disasters, the Livestock Forage Program (LFP), and some other assistance programs. While I do like the drought monitor system, there are some problems with it. It is hard to take account both surface allocations for irrigated agriculture and non-irrigated areas such as rangelands and meadows when determining where the designation lines should be. Thus, there is some subjectivity in where those lines are drawn and now those lines directly impact agriculture assistance payments. I have also heard that there was some talk about determining AUMs based on the monitor and my colleagues (Perryman and Schultz) have published on this topic.

I hope everyone has their management plans in place. According to Washington State University Economist Shannon Neiburgs, 63% of the US is under some form of drought. The Southwest and southern Rocky Mountain regions have been in drought for many months and face limited forage prospects this year unless precipitation occurs soon. In the Northern Plains, North Dakota is in a record level drought and South Dakota drought conditions are worsening. I would end with saying, in Nevada, drought conditions continue to worsen.

By Staci Emm | Editorial