Lessons From Maggie Creek

Lessons From Maggie Creek

For this year’s summer field tour the Nevada section of the Society for Range Management (NVSRM) had the pleasure of co-hosting the event with the ROGER (Results Orientated Grazing for Ecological Resilience) group. While there is a lot of shared membership between NVSRM and ROGER , this was their first joint meeting. Meghan Brown, 2022 president-elect of NVSRM, organized an amazing program that was attended by producers, resource agencies, researchers from the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) and other interest groups.

The event took place July 12-13 at Maggie Creek, north of Carlin, Nevada. This riparian area is decades into recovery after the creek was channelized for irrigation. Maggie Creek now meanders and flows naturally, creating a diverse riparian ecosystem. The focus of the field tour this year was Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (LCT) monitoring, although is impossible not to discuss cheatgrass, fuels and fire on any field tour in Nevada.

We started the day by observing a targeted grazing study area in an 8-acre exclosure along Interstate 80. Jon Griggs, who manages the Maggie Creek Ranch, explained how the project began. Pat Clark from USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Boise Idaho reached out to Jon about adding this site to their targeted grazing research program in Idaho and Nevada, the closest site being on the TS Ranch property just to the west. Jon explained some of last year’s grazing treatments, which involved about 100 cows stocked in either spring or fall/winter when the cheatgrass had senesced. Jon described the difficulty of hitting the window of cheatgrass greenness in spring which, coupled with the varying height of cheatgrass year to year, made spring grazing difficult. He found it easier to graze the dried cheatgrass fuel off the site in fall/winter because it can be done anytime during that period. Grazing during fall/winter helps remove dry carryover fuels. Hanes Holman, local Carlin rancher, began the TS Ranch targeted grazing project. Hanes, who is the 2022 NV Cattlemen’s Association president-elect, gave a brief background on that project.

Chris Jasmine, with Nevada Gold, currently oversees the TS Ranch project, pointed to recent fires that were stopped at the targeted grazing strip. He said the fires don’t stop on the grazed fire breaks but the decrease in fuel changes the fire’s behavior enough to buy time for the fire crew to stop them at the fuel breaks. Chris explained that the purpose of the targeted grazing is not to restore the perennial plant community, or rehab the site, but solely to remove or reduce fuels enough to change fire behavior and increase chances to stop them.

Jon explained that the 8-acre project cost about $1,500 to $3,000 for water, supplements and moving the animals at the site, which would be $180 to $375 per acre. He said many factors influence the cost, and each site is different. For instance, traditional use of herbicide (imazapic) to control dry cheatgrass fuels cost around $20 per acre. He added that having multiple options to control fuels and decrease fire threats is the best strategy to conserve rangelands.

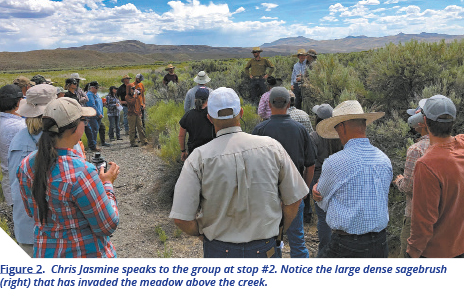

The next stop was a lower section of Maggie Creek, where Chris Jasmine discussed adaptive management in annually changing environments. Chris highlighted the importance of not only having adaptive management when something has worked poorly or failed, but also having options ready when things go better than expected. He explained that this site had been rested from grazing to support the plants’ recovery, but the plants were more productive than expected and he wondered if some grazing would be a good thing at this point. He stressed the importance of considering not only resting grazing but also increasing grazing to achieve conservation objectives. This section of riparian corridor of Maggie Creek had recovered so well that the cattails had returned and water holding had drowned out the willows, so it resembled a wide (100 feet) marsh full of cattails and other wetland plants. Jon joked that “it is not a good day” when an animal wonders out in the marsh and has to be rescued.

The upper terrace meadow we were standing in, above the cattail marsh and creek, was heavily invaded by Basin Big Sagebrush that was quite old with large trunks standing 6 feet tall. There was a brief discussion on methods of sagebrush control to release the meadow herbaceous understory plants. The group covered the pros and cons of using mowing, crushing or herbicides to control the sagebrush. It was thought the most effective and economical method would probably be a 2-4D treatment to control the sagebrush and the rabbitbrush; rabbitbrush can’t be controlled with mowing or crushing like sagebrush.

We walked half a mile along the creek through a dense, sagebrush-invaded meadow. We saw understory areas dominated by creeping wildrye and juncus and drier areas where cheatgrass had invaded. Beaver dams along the creek had increased the water holding capacity. We even saw evidence of beaver chewing on large sagebrush trunks along the creek.

Our next stop was a water gap area where livestock have access to Maggie Creek. Jon Griggs discussed the importance of having access to the creek for water and the benefits of water gaps to help address the challenges associated with managing livestock grazing to maintain or improve riparian habitats. Paul Meiman, associate professor with UNR Extension, discussed the differences between short-term and long-term monitoring and how both are required to ensure proper management decisions. This discussion focused on livestock grazing for riparian and LCT habitat. He reminded the group that when it comes to livestock grazing management, the problem of relying too heavily ,or entirely, on short-term indicators and not enough on long-term indicators has been an ongoing challenge. Paul summarized a 70-year history of problems, from attempting to manage livestock grazing based only on utilization (one form of short-term monitoring) and explained that very similar problems would likely occur for other types of short-term targets (stubble height, woody plant utilization and streambank alteration) if too much, or all of the emphasis is placed on those. The intent was to brainstorm ways to avoid this problem and ensure that a mix of short-term and long-term indicators guides management.

The group discussed monitoring techniques and combinations of indicators that might be helpful to estimate animal use and its impact on the riparian area through time. For example, stubble height and streambank alteration (hoofprints) are 2 short-term indicators that could be combined with one or more long-term indicators such as measurements of stream width (greenline to greenline) to provide valuable information for managers. Dr. Tamzen Stringham, a riparian ecologist at UNR, said the effectiveness of current monitoring measurements used by the Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) could be improved by choosing monitoring methods appropriate for specific stream types instead of a standardized, one-size-fits-all approach. The USFWS challenged that notion and argued their appropriateness. Dr. Stringham clarified her comments noting that the short-term indicator of bank damage may be appropriate for low gradient, sedge dominated streams but is ineffective for high gradient, willow lined channels. The local BLM office stated there were concerns on what monitoring was best but overall the current methods seemed to be effective. Dr. Stringham voiced her concern that BLM does not have the manpower to monitor; therefore they contract out monitoring to individuals who may not have the skill set necessary to collect quality monitoring data. Laura Van Riper, with the BLM’s National Riparian Service Plan, suggested that Dr. Stringham and Dr. Meiman get together with USFWS and the BLM to determine the most effective monitoring methods to ensure the best management of riparian resources.

Further upstream we saw where a beaver dam had increased the depth of the creek. Beaver ponds that form upstream of each dam retain water during wetter parts of the year. During drier parts of the year, they gradually release that water into nearby soil where it is accessible to the roots of riparian vegetation. The creek meandered quite a bit in this area with some sections having deep incised sides on large downstream bends. Jon explained that the creek and riparian corridor was previously in poor condition, not so much because of the grazing regime but because the creek was channelized for irrigation purposes. That practice of creating straight irrigation channels, and removing the water from the natural flow of the creek, heavily degraded the riparian system. Once the creek was returned to its natural flow regime, the recovery process began. Willows returned and then beavers began to use the creek, which increased water holding capacity, and riparian plant communities began to develop and function.

At this stop we discussed the effect that fire and the subsequent cheatgrass dominance on the surrounding, more arid hill slopes can have on the riparian system. Jon showed a map with past fires in the area. The fires covered a significant part of the landscape and surrounded where we were standing. One fire burned right across the creek and spread to the foothills on the other side. T.J. Thompson from the Kings River Ranch explained that while the riparian areas in his allotments get a lot of attention and are critically important, they represent only maybe 5% of the landscape and we can’t focus on them alone. The other 95% of the landscape that is often at risk of fire and annual grass invasion is also critically important to the ecosystem function and if degraded can negatively affect the riparian areas.

At this stop we began to notice the Mormon crickets that blanketed the vegetation along the creek, like an apocalyptic scene from a movie. In drought years the crickets can have population outbreaks in Northern Nevada and cause significant damage to plant communities. Before moving to the next site, we all did a quick cricket check to clear off any unwanted passengers.

We finished the day at Maggie Creek Ranch’s Red House Unit, a few miles north from our last stop, discussing the topics of the day over an amazing dinner featuring Maggie Creek Ranch brisket. NVSRM presented Jon Griggs and the ROGER group with a stewardship award for their continued dedication to resource conservation and supporting rangeland ecology sciences. Kevin Ahearn, the manager at Red House, and his crew were amazing hosts for the evening as the sun set and we made for the campsite, a mile up the creek.

The following morning we continued the tour at a site near camp, that had been seeded to crested wheatgrass after a fire in the late 1970s. Jon pointed out that this site was now dominated by sagebrush with a sparse crested wheatgrass understory and interspace. This led to a discussion about what promotes sagebrush return in crested wheatgrass or any perennial grass dominated plant community.

Dr. Stringham explained that heavy spring grazing, for multiple years in a row, of perennial grass should decrease site competitiveness of the perennial grasses and promote faster sagebrush return as long as there is a sagebrush seed source (mother plants) present. Dan Harmon of the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Reno, explained that the literature describes how many plant communities in the arid regions of the Great Basin are shrub dominated, with perennial grass being sub-dominant, because the shrub’s deep tap root can help it survive, giving it an advantage over the shallower rooted perennial grasses. In the Columbia Plateau region, in areas like southern Idaho, with favorable soils and wetter conditions than the Great Basin, the perennial grasses dominate and shrubs are sub-dominant. These differences can be observed on the landscape with the hundreds of thousands of acres historically seeded to crested wheatgrass in Nevada that are now dominated by sagebrush with little crested wheatgrass remaining along U.S. 50 east of Austin, Nevada, as well as many areas in Northern Nevada. It was noted that in Idaho, areas dominated by crested wheatgrass or bluebunch wheatgrass have had very slow shrub return.

Next we stopped near a section of Maggie Creek that had large culverts used as fish ladders to help Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (LCT) movement and to help with movement of water for irrigation of the meadows. Jon Griggs showed pictures of the last big flood that had washed the culverts out and the improvements made to them to hopefully avoid the damage with the next flood event. Jason Barns with Trout Unlimited explained the importance of this section of the creek to spawning movement. He explained how they monitor the gene pool of the fish along the creek to ensure there is good fish movement and genetic diversity among all the populations along the creek. The group discussed what makes good habitat for the LCT and how to monitor or evaluate habitat condition. Melany Aten with the Nevada Association of Conservation Districts (NVACD) asked if USFWS had heard any concerns from producers that if LCT was introduced into a waterway they were using, it could lead to restricted use of that area. Sean Vogt, with USFWS, explained that LCT are released only into waterways that are appropriate for their survival, and properly managed livestock use that results in properly functioning riparian ecosystems shouldn’t create conflict with LCT management or result in restrictions to the livestock operation.

A discussion ensued about the best indicators of a well functioning creek. The group thought that indicators that were more long term and less affected by the current year’s weather conditions were best. The group had a discussion of the appropriateness of using water temperature as an indicator that could restrict livestock use of the area, since it is so highly variable based on the time of year and seasonal weather conditions. Jason explained that staying below a specific temperature was critical to LCT survival, so it is a necessary monitoring measurement but shouldn’t be the main indicator for restricting riparian area use by animals. There was a small debate whether or not USFWS recommends the BLM include water temperature in their monitoring protocols. Sean believed it wasn’t typically included as a restricted use indicator. However, the local BLM thought that it was often recommended for use as an indicator and gave some examples when it was used. Both folks agreed that the agencies should further discuss their concerns in regard to riparian ecosystem health and function monitoring.

The final presentation occurred back at the Red House Ranch where we enjoyed some shade. Hondo Brisban, a UNR graduate student in Dr. Stringham’s lab, presented some of the research he and others from UNR are doing at Maggie Creek. Hondo is collecting data on soil carbon storage, a popular topic due to climate and carbon emissions concerns. He gave an overview of the research and some preliminary results that he is using to work toward creating a model to predict carbon storage in these systems. The general pattern with carbon storage is that the more plant roots in the soil, the more carbon makes its way into the soil to be stored. Based on Hondo’s study, as you go upstream along the creek and water increases along with plant community productiveness, so does soil carbon storage.

We finished the tour with everyone giving a brief statement of what was best about the meeting. A common thread was the appreciation for the participation of the attendees and a feeling of stewardship concern, cooperation and collaboration from all.

NVSRM would like to thank the ROGER group, the hosts and all the participants for a fun and informative field tour.

By Dan Harmon and Meghan Brown