This is the first part of a three-part series focusing on improving mule deer populations on Nevada rangelands.

In more recent times, it has been quite obvious that game species such as sage grouse have received enormous attention and financial obligation in an effort to restore and protect this sensitive species. Yet, the only declining big game species in North America, mule deer, are largely absent from the concern of most researchers. The vocal sentiment of many sportsmen and women in northern Nevada, concerning mule deer, is one of frustration. As other big game species such as pronghorn, elk and bighorn sheep continue to experience growth and expansion, mule deer on the other hand continue to struggle overtime.

Historically, most authorities agree that at the time of European contact in northern Nevada, mule deer were in fact quite scarce. Early explorers like Jedidiah Smith, Peter Skene Ogden, and John Work journeyed throughout the Great Basin during the second and third decades of the 19th century. Their journals indicate that few mule deer were encountered. Despite these mountain men being the epitome of professional hunters, they often found themselves hungry and sometimes killed their own horses to survive. Early explorers were known to have to survive by drawing blood from their stock and making a blood pudding as well as sticking their hands down ant mounds and licking the ants for much needed protein. John Work described in November 1832 in northwestern Nevada, “few tracks, but no site of deer”. “Crossing the road was a singular barrier, built by Indians, to pen in, probably, large hares when they hunt them, for there is no other game here” reported Bruff on 25 September 1849 while traveling near Soldiers Meadows in northwestern Nevada. These early explorers and trappers noted the abundance of pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep and waterfowl in certain areas, but quite often noted the scarcity of mule deer throughout their travels. The areas where these early explorers and trappers traveled and recorded the scarcity of mule deer supported mule deer by the thousands by the mid-1950s and through the 1980s. Now, a half a century later, mule deer are experiencing declining herds. Mule deer are browsers and therefore benefit when shrub species such as big sagebrush, curl leaf mountain mahogany, antelope bitterbrush and other woody species are productive components on their ranges. These woody species are beneficial as they provide desired nutrition and cover. This does not exclude the nutritional importance of forbs and early growth grasses to the well-being of mule deer as these are preferred forages during spring and early summer months. But, as fall and winter months arrive, much needed digestible protein and cover provided by shrub species can be the difference between survival and death (Figure 1).

Historically, most authorities agree that at the time of European contact in northern Nevada, mule deer were in fact quite scarce. Early explorers like Jedidiah Smith, Peter Skene Ogden, and John Work journeyed throughout the Great Basin during the second and third decades of the 19th century. Their journals indicate that few mule deer were encountered. Despite these mountain men being the epitome of professional hunters, they often found themselves hungry and sometimes killed their own horses to survive. Early explorers were known to have to survive by drawing blood from their stock and making a blood pudding as well as sticking their hands down ant mounds and licking the ants for much needed protein. John Work described in November 1832 in northwestern Nevada, “few tracks, but no site of deer”. “Crossing the road was a singular barrier, built by Indians, to pen in, probably, large hares when they hunt them, for there is no other game here” reported Bruff on 25 September 1849 while traveling near Soldiers Meadows in northwestern Nevada. These early explorers and trappers noted the abundance of pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep and waterfowl in certain areas, but quite often noted the scarcity of mule deer throughout their travels. The areas where these early explorers and trappers traveled and recorded the scarcity of mule deer supported mule deer by the thousands by the mid-1950s and through the 1980s. Now, a half a century later, mule deer are experiencing declining herds. Mule deer are browsers and therefore benefit when shrub species such as big sagebrush, curl leaf mountain mahogany, antelope bitterbrush and other woody species are productive components on their ranges. These woody species are beneficial as they provide desired nutrition and cover. This does not exclude the nutritional importance of forbs and early growth grasses to the well-being of mule deer as these are preferred forages during spring and early summer months. But, as fall and winter months arrive, much needed digestible protein and cover provided by shrub species can be the difference between survival and death (Figure 1).

Among the hypothesis for the mule deer population irruptions of the 1950s, U.S. Forest Service Researcher, George Greull reported in his publication “Post-1900 mule deer irruptions in the Intermountain West; Principle causes and influences” that the environmental changes brought about by domestic livestock grazing resulted in the decrease of herbaceous species, decrease in wildfire frequencies due to decreases in herbaceous fuel loads and the significant increase in shrub species that benefitted mule deer throughout the Great Basin. Pioneer range scientist, James A. Young pointed out that virtually all western Great Basin plant communities that had sagebrush species during this mule deer irruption had sagebrush species under pre-contact conditions. Young also pointed out that even though these shrub species were present during pre-contact time, a very subtle increase in shrub communities could have significant beneficial impacts on browsing ungulates such as mule deer.

Mule deer population estimates reported less than 50,000 animals in the early 1900s, followed by irruptions of an estimated 250,000 animals by 1950 and 240,000 in 1988. Since 1988 there has been a gradual decline in mule deer populations with an estimated population of 92,000 by 2020. With this prolonged and continual decline in mule deer populations has come the numerous justifications for these experienced declines, from multiple habitat issues such as wildfires (Figure 2) and drought to lack of predator management. There is no shortage of finger pointing and emotions are running high, nonetheless, mule deer populations continue to experience declining conditions. The majority of wildlife biologists focus their concern on habitat, as they should, yet concerned sportsmen and women also have voiced their concern on the lack of predator control and the negative impact that predators can have on limiting mule deer populations and recovery.

Mule deer population estimates reported less than 50,000 animals in the early 1900s, followed by irruptions of an estimated 250,000 animals by 1950 and 240,000 in 1988. Since 1988 there has been a gradual decline in mule deer populations with an estimated population of 92,000 by 2020. With this prolonged and continual decline in mule deer populations has come the numerous justifications for these experienced declines, from multiple habitat issues such as wildfires (Figure 2) and drought to lack of predator management. There is no shortage of finger pointing and emotions are running high, nonetheless, mule deer populations continue to experience declining conditions. The majority of wildlife biologists focus their concern on habitat, as they should, yet concerned sportsmen and women also have voiced their concern on the lack of predator control and the negative impact that predators can have on limiting mule deer populations and recovery.

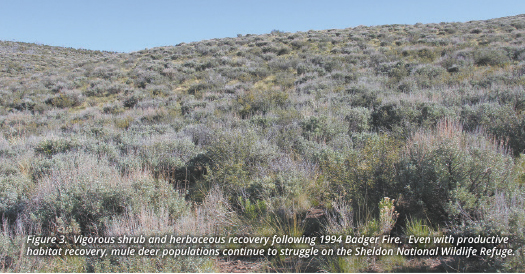

As an anecdotal, I remember the winter of 1992-1993 that was so devastating to mule deer herds throughout Nevada. Although this is just a snap shot in time review and site selective, two important things were occurring in northwestern Nevada that are of interest. First, in 1991, livestock were removed from the Charles Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge managed by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Refuge, located in the far northwestern portion of Nevada, is over 570,000 acres of a variety of habitats ranging from salt desert shrub and xeric Wyoming big sagebrush to mountain brush communities. This is important to mention because at the time of removing domestic livestock, representatives from state, federal and private organizations were in fact blaming livestock grazing for habitat destruction that negatively impacted wildlife species, such as mule deer. The late University Nevada Reno Biology Professor, Peter Brussard, was instrumental in the Charles Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge scientific working group in the 1990s following the removal of domestic livestock. Of the indicator species that Peter selected to track rangeland health, from the perspective of removing domestic livestock, was mule deer. Following the 1992-1993 winter that resulted in heavy mortality of mule deer herds, there was an initial rebound in the state mule deer population from 115,000 in 1994 to 134,000 in 1999. On the Charles Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge, the 1999 post-season composition survey resulted in the classification of 330 mule deer with a composition of 49 bucks/100 does/85 fawns and a tag allocation of 133 mule deer tags. Twenty years later in 2019 the post-season survey resulted in 112 mule deer with a 33 bucks/100 does/44 fawns with a tag allocation of 46. Why is this important? Experts assured all involved parties including sportsmen and women that the removal of domestic livestock would result in healthier range conditions which would result in an increase in wildlife indicator species such as mule deer (Figure 3). The fact is that this intense management decision did not result in a population increase of mule deer on the Refuge.

As an anecdotal, I remember the winter of 1992-1993 that was so devastating to mule deer herds throughout Nevada. Although this is just a snap shot in time review and site selective, two important things were occurring in northwestern Nevada that are of interest. First, in 1991, livestock were removed from the Charles Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge managed by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Refuge, located in the far northwestern portion of Nevada, is over 570,000 acres of a variety of habitats ranging from salt desert shrub and xeric Wyoming big sagebrush to mountain brush communities. This is important to mention because at the time of removing domestic livestock, representatives from state, federal and private organizations were in fact blaming livestock grazing for habitat destruction that negatively impacted wildlife species, such as mule deer. The late University Nevada Reno Biology Professor, Peter Brussard, was instrumental in the Charles Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge scientific working group in the 1990s following the removal of domestic livestock. Of the indicator species that Peter selected to track rangeland health, from the perspective of removing domestic livestock, was mule deer. Following the 1992-1993 winter that resulted in heavy mortality of mule deer herds, there was an initial rebound in the state mule deer population from 115,000 in 1994 to 134,000 in 1999. On the Charles Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge, the 1999 post-season composition survey resulted in the classification of 330 mule deer with a composition of 49 bucks/100 does/85 fawns and a tag allocation of 133 mule deer tags. Twenty years later in 2019 the post-season survey resulted in 112 mule deer with a 33 bucks/100 does/44 fawns with a tag allocation of 46. Why is this important? Experts assured all involved parties including sportsmen and women that the removal of domestic livestock would result in healthier range conditions which would result in an increase in wildlife indicator species such as mule deer (Figure 3). The fact is that this intense management decision did not result in a population increase of mule deer on the Refuge.

Secondly, another event that occurred, was in 1990 when mountain lions became a “specially protected species” in California. Again, this is only a snap shot in time and is focused on western Nevada mule deer populations rather than the whole state. Brent Espil of the John Espil Sheep Company has mentioned on numerous occasions through personal discussions that mountain lions were not much of a problem in the habitats where he runs cattle and sheep, but by 1993 and 1994 mountain lion predation on his sheep herd had become very evident as well as the numerous sightings of mountain lions throughout his range which just a few years earlier was nearly absent. This increase in mountain lion presence was soon to be witnessed throughout western Nevada hunting zones. Rick Sweitzer, University Nevada Reno PhD student in the 1990s was conducting research in Granite Basin just north of Gerlach, NV on porcupines. At the time it was believed that this part of the Granite Range in northern Nevada held the largest known population of porcupines in North America. Rick reported that by 1997 the porcupine population had been decimated by mountain lion predation. Given that my background and training are in wildlife management, it is not uncommon to have wildlife managers believe that predator populations follow the cycles of their prey, therefor when a mule deer population or porcupine population decline the predator population will decline as well and not rebound until after the prey base has rebounded. Perhaps one of the problems with this line of thinking is the overall prey base. Predators can seek out their preference, such as bighorn sheep or mule deer, but also count on other prey such as porcupines or domestic livestock, therefor become a potential limiting factor to population recovery following favorable habitat scenarios.

There is no doubt that when looking at issues that challenge the restoration of mule deer populations numerous opinions and concerns arise, yet to open this dialog and perhaps open the minds to the opinion of others even though it may not be your own is indeed a dialog worth having.

By Charlie D. Clements