Click on images above to view larger.

Part 2 of a three-part series focusing on improving mule deer populations on Nevada rangelands.

Part 2 of a three-part series focusing on improving mule deer populations on Nevada rangelands.

This is the second part of a three-part series focusing on the need to improve mule deer populations. The first series pointed out the historical mule deer populations from very low numbers to record numbers and eventually a continued decline. Mule deer are the only declining big game species in North America, hopefully engaging in this topic will bring about added ideas and approaches to improving mule deer populations not just in Nevada, but throughout the West.

In big sagebrush communities, wildfires are the primary stand renewal process. Excessive grazing reduced grasses and brought about the reduction in fine fuels to carry wildfires. The shrubs then became larger, more vigorous, and established in higher densities. This vegetation change was beneficial to mule deer herds throughout the West. In more than a century, big sagebrush plant communities in the Great Basin have gone through periods of:

1) pristine wildfire frequency with aboriginal burning,

2) promiscuous burning,

3) attempted complete suppression of wildfires, and

4) attempts at prescribed burning and let-burn policies for wildfires.

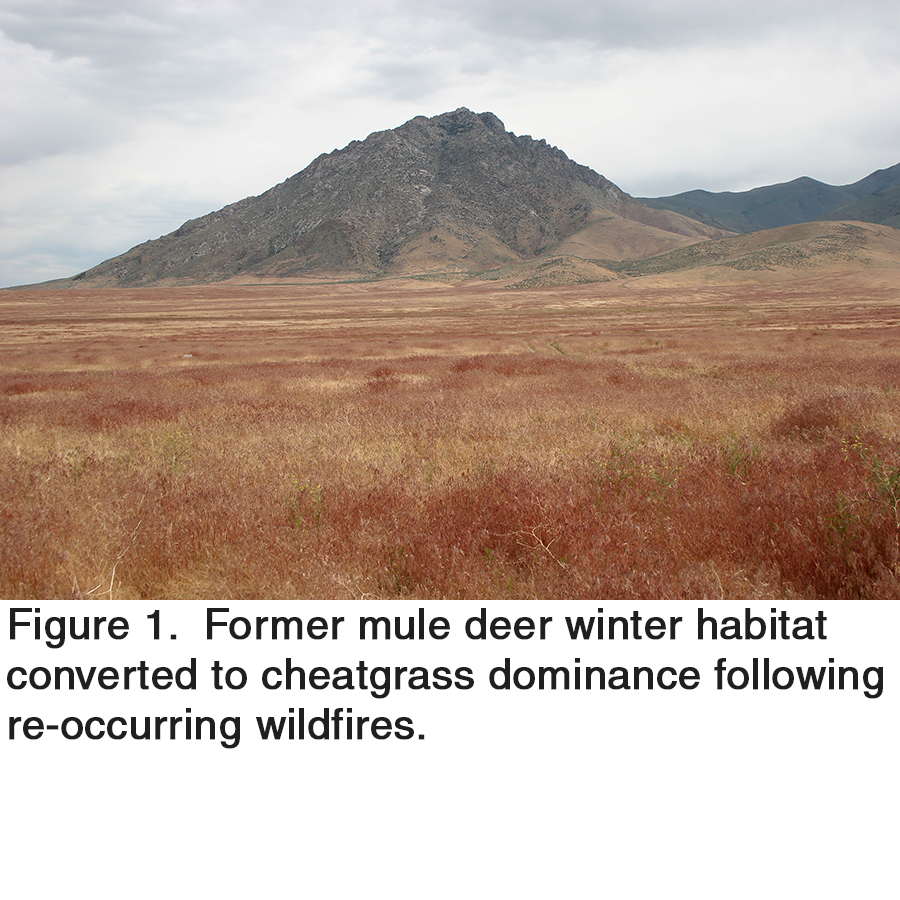

Historically, wildfires in the northern Great Basin experienced wildfire intervals of every 60-110 years and mostly occurred in the late summer after the perennial grasses had flowered and dried out. The accidental introduction of cheatgrass and its’ subsequent invasion onto millions of acres of Great Basin rangelands has increased this wildfire interval to a reported 5-10 years. Aldo Leopold, in 1949 recognized this problem and how impossible it is going to be to protect wildlife habitat from cheatgrass fueled wildfires. The accidental introduction and subsequent invasion of cheatgrass indeed contributed significantly to the transformation of millions of acres of wildlife habitats throughout the West, especially browsers such as mule deer. Cheatgrass outcompetes native plant seedlings for limited moisture and nutrients resulting in less perennial species recruitment and more cheatgrass that provides a fine-textured early maturing fuel that increases the chance, rate, spread and season of wildfire. With each passing wildfire season more and more critical shrub communities are burned and converted to cheatgrass dominance (Figure 1 above). When cheatgrass moves in, wildfires that destroy shrubs follow. This scenario has played out all across the Intermountain West, which now is experiencing larger and more frequent wildfires at alarming rates. You can pick numerous large wildfire complexes in the Great Basin that have been significantly destructive to mule deer, such as those wildfires in northeastern Nevada that burned 300,000 acres in 1964, another 778,000 acres (1,171 square miles) between 1999 and 2001 from Battle Mountain to Elko, the Holloway Fire in 2012 that consumed 462,000 acres and the Fire Martin Fire 439,230 acres in 2018 just to name a few. Shrub species simply do not have enough time to recover from large and frequent wildfires which has led to the conversion of millions of acres of big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities to cheatgrass dominance.

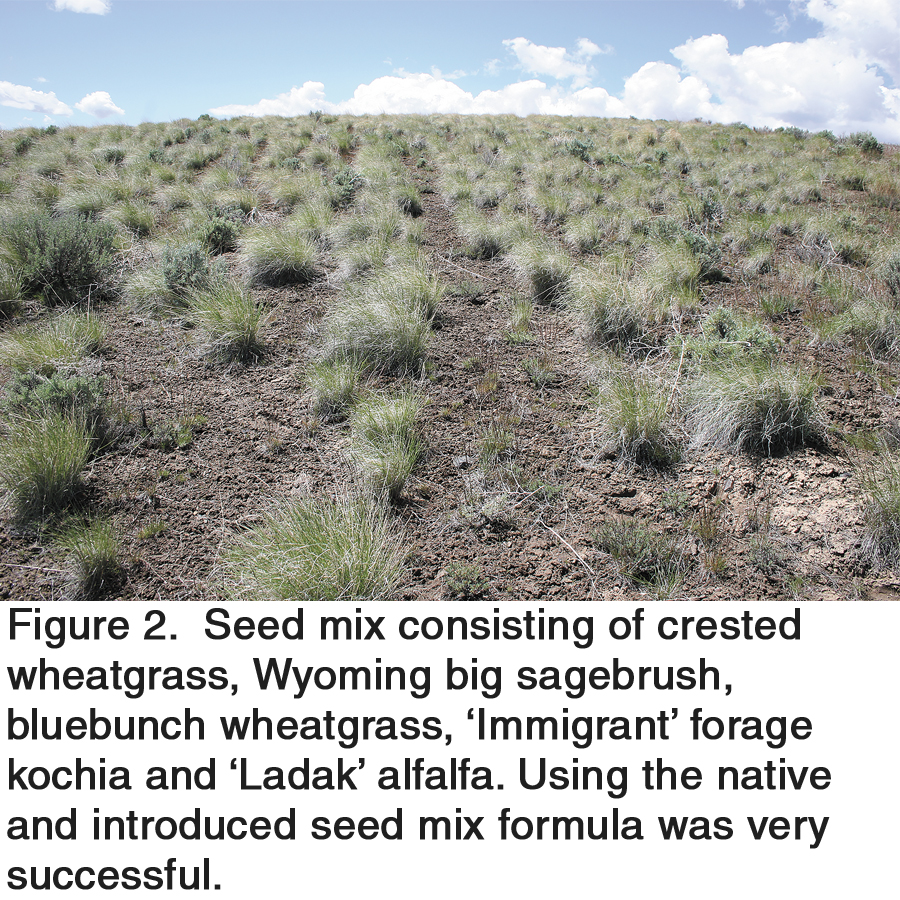

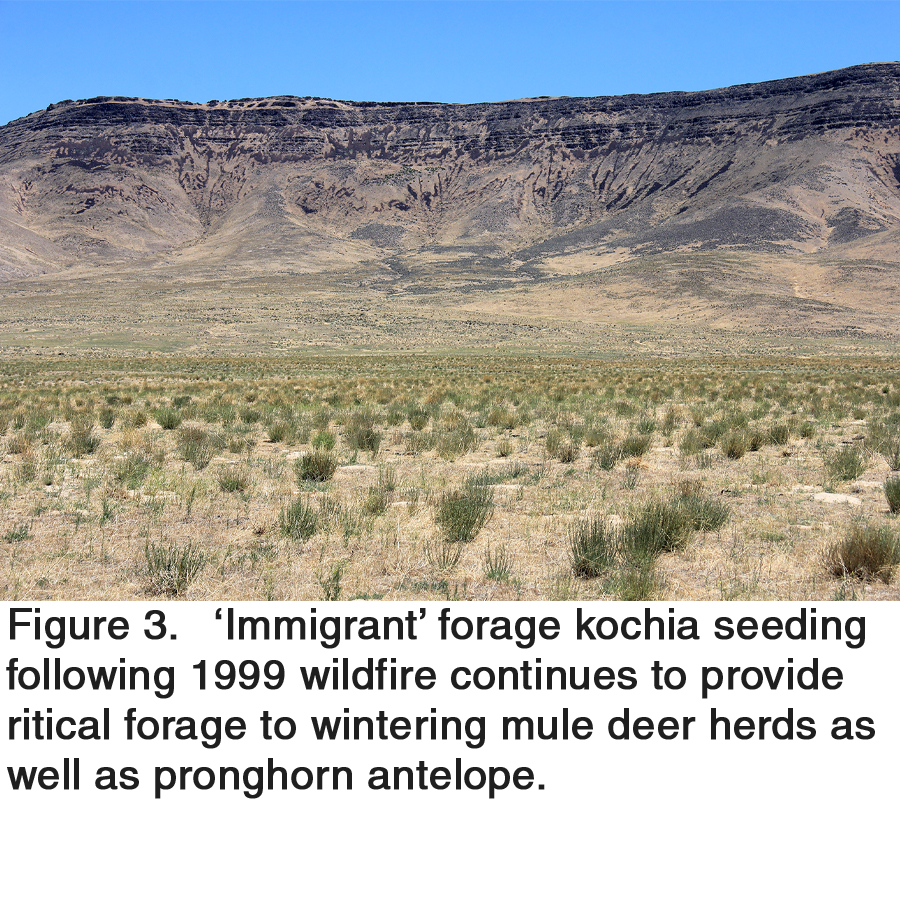

Ken Gray, retired Nevada Department of Wildlife biologist, and Tom Warren, retired Emergency Stabilization and Rehabilitation Operations Manager, both out of Elko, Nevada recognized the threat of wildfires to wildlife habitats in the early 1990s and started aggressive rehabilitation projects in northeastern Nevada. Wildfires were significantly impacting wildlife habitats, specifically mule deer transitional and winter ranges in which the mule deer populations in that region had significantly declined. Taking advantage of mining mitigation funds, contributions from sportsmen groups and consulting with experienced researchers, rehabilitation projects aimed at preventing wildfires while at the same time providing forage hit the ground running. Most rehabilitation seedings at that time included numerous diverse plant species of grasses, shrubs and forbs which resulted in 8-12 species in a single seed mix. The publication, “Restoring Big Game Range in Utah” authored by pioneer researcher Perry Plummer in 1968 became very popular among resource managers and was heavily relied on for guidance in restoring and rehabilitating rangelands throughout the Intermountain West. Perry recommended that managers seed 4 grasses, 4 shrubs and 4 forbs in their seeding efforts to add diversity and much needed nutrition. One of the problems with this prescription is that most of the research behind this recommendation occurred in southwest Utah where summer precipitation is very favorable. In the northern Great Basin and much of Nevada, the precipitation is quite different and categorized as the Cold Desert where the vast majority of precipitation occurs during the winter months. Although there was discussion to follow such a recommendation, Ken Gray and Tom Warren reduced the number of species to be seeded and focused on plant materials that could germinate, emerge and establish in the face of cheatgrass competition following weed control practices while at the same time providing perennial forage. The use of introduced plant species crested wheatgrass and forage kochia were the two main species used in these efforts and resulted with increased success. Due to pressure from environmental groups, there was lapse in herbicide research from the 1980s to the late 1990s, so their method was to disk the site in the spring before cheatgrass flowered, fallow the site through the summer and then seed the site in the fall. Deep-rooted perennial grasses, such as bluebunch wheatgrass and crested wheatgrass, are the best-known method at suppressing cheatgrass densities and associated fuels. Crested wheatgrass was initially brought over to plant in Halogeton infested habitats and was quickly learned to be successful in arid environments that included cheatgrass. ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia was initially brought over to the United States from Russia in the early 1960s and later approved as a rehabilitation species in 1986. The use of crested wheatgrass was aimed at competing with and ultimately suppressing cheatgrass densities and associated fuels, while the use of ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia was used to provide a much needed and excellent nutritional value as well as taking advantage of this plants ability to establish in arid environments on a variety of soil types, stay green through the summer months (decreasing chance of ignition), and resprout following wildfire. Ken Gray and Mark Warren, in conversation with researchers and other practitioners, relied heavily on these two species in their seed mix prescriptions which also included native bunchgrasses, big sagebrush and forbs (Figure 2 above). In less than a decade their hard work started to pay off as the successful seedings became food plots to not just mule deer, but pronghorn antelope and elk as well. The initial establishment of these seedings reduced cheatgrass densities and associated wildfire threats and proved to provide significant forage for mule deer (Figure 3 above) that resulted in a decrease in winter mortality of mule deer and an increase in the mule deer population.

Another habitat conversion that has occurred includes the encroachment of pinyon-juniper woodlands into many habitats that have significantly reduced herbaceous and browse species and the recruitment of these species. Pinyon and juniper encroachment have been particularly difficult for resource managers in the central and eastern portions of Nevada. This encroachment not only has crowded out herbaceous and browse species, it has also negatively impacted natural springs and meadows. An estimated 18 million acres of rangelands in various successional stages have been invaded, three times that amount that was present at the time European contact. When these pinyon-juniper habitats burn or are manually cleared they usually return to perennial grass dominance and productive shrub communities. The improvement of habitats throughout the rangeland will benefit not only mule deer, but wildlife in general. The more vigorous and nutritional habitats that are available the less impact that drought, wildfire, winter and predation will have on the health of Nevada mule deer herds. Starker Leopold recommended more than a half century ago that to maintain high carrying capacities of mule deer deliberate manipulation of plant succession must be implemented. When habitats are successfully treated and establishment of vigorous and nutritional plants occur it is not only important to practice proper grazing management, it is also important to protect from wildfires where appropriate but also conduct aggressive predator management as to allow these species to rebound without high levels of predation.

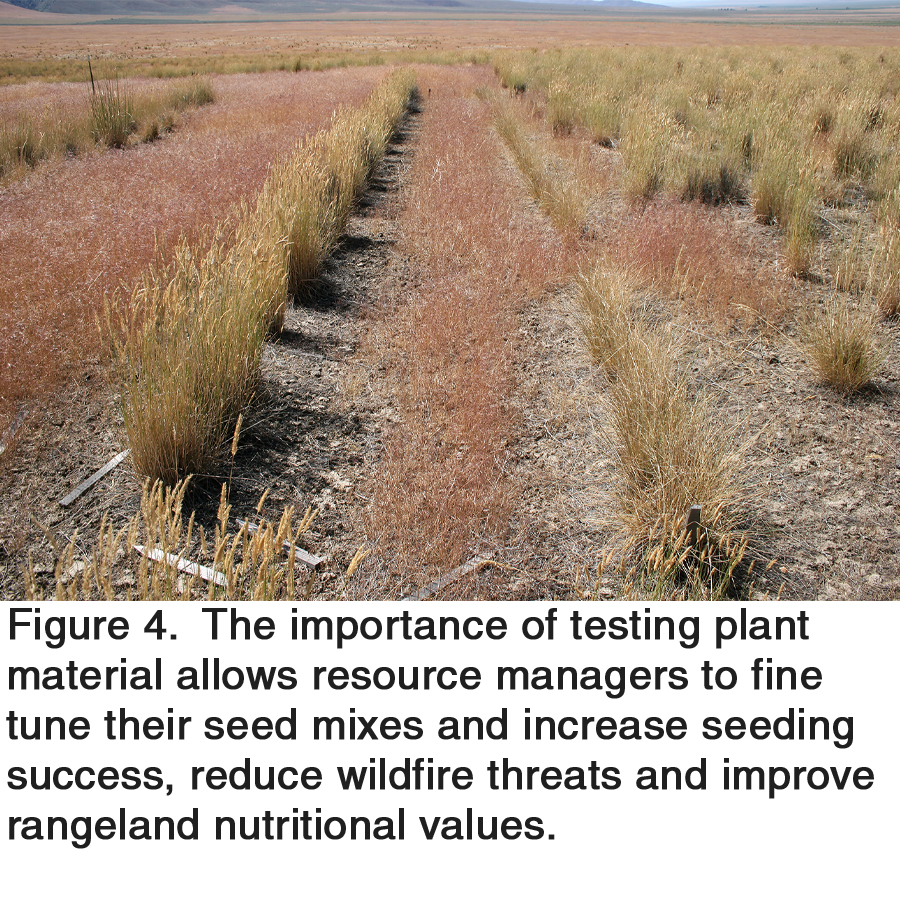

In more recent times there has been an aggressive push through the National Seed Strategy for Rehabilitation and Restoration to seed genetically appropriate native seed species to build ecological resilience. The growing popularity in this strategy has resulted in increased frustration by resource managers that differ in their experience when attempting rehabilitation and restoration practices following wildfires and other disturbances. They do not object to using native species, but would like to hedge their bet in the seed mix by still including proven species that may be native but perhaps not native to that site, or introduced species such as crested or Siberian wheatgrass and forage kochia. The lack of genetically acceptable native seed source for large wildfires is also quite limiting and of concern. The lessons learned by individuals like Ken Gray and Tom Warren would be erased from on the ground realities to achieve this strategy. Introduced weeds such as cheatgrass, medusahead and Russian thistle to name a few evolved in environments much like the Great Basin, using genetically appropriate seed to compete with and suppress these aggressive and successful weeds may not lead to the success that is promised. This approach must be experimented with both at the plot level (Figure 4 above) as well as larger demonstration plots (Figure 5 above) to gain knowledge on what works and what does not work in these harsh arid environments. In 1826, at the present location of Malheur Lake in east-central Oregon, Peter Skene Ogden wrote, “I may say without exaggeration, man in this country is deprived of every comfort that can tend to make existence desirable. If I escape this year I trust I shall not be doomed to endure another.” Resource managers attempting to restore Great Basin rangelands often focus their efforts on establishing plant species that are native, beneficial to wildlife, and represent pristine conditions. As the journals of early explorers note, pristine habitats and mule deer were apparently not compatible in the Great Basin.

By Charlie D. Clements