Big sagebrush habitats are one of the largest and most threatened ecosystems in North America. With the accidental introduction and invasion of the exotic annual cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) there has been an increase the chance, rate, spread and season of wildfires which has resulted in drastically altered big sagebrush communities.

With each passing wildfire season more and more sagebrush is lost, leading to a progressive conversion to cheatgrass-dominated plant communities that lack any shrub component.

Big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) is not a fire-tolerant species. Big sagebrush does not resprout after fire and often must be restored through seeding or transplanting efforts. In higher elevations dominated by mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata subsp. vaseyana), the cooler, wetter climate significantly improves successful seeding efforts. In contrast, the more arid climate of the lower elevation Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata subsp. wyomingensis) habitat makes successful seeding efforts very difficult.

It is common for the Bureau of Land Management to spend the most funds on sagebrush seed and seeding efforts in any given year compared to other native plant species in restoration efforts. The wildlife that relies on sagebrush is often left with an “empty plate” after wildfires, increasing the need for a shrub component for critically important browse and cover.

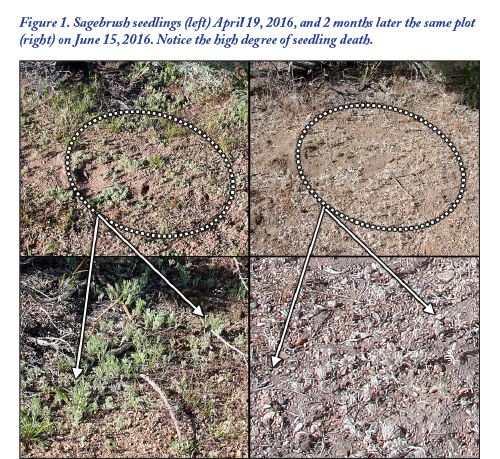

Sagebrush is a unique species in that it produces millions of tiny seeds, unlike other browse species such as antelope bitterbrush (Pursia tridentata), 4-wing saltbush (Atriplex canescens) which produce much larger seeds. These tiny seeds rain down below the canopy of the sagebrush, and if conditions are right, a mat of tiny seedlings emerge. Small seedlings from tiny seeds, however, require a prolonged period of soil moisture to survive, and the fate of most if not all the seedlings is often desiccation leading to increased mortality of the seedlings (Figure 1).

If the high volume of sagebrush seeds that fall below a plant leads to infrequent seedling recruitment, then restoration seeding efforts that typically broadcast 1/10th of a pound per acre of seed have even less frequent establishment.

This high percentage of failure for sagebrush seeding efforts makes the need for a dependably seeded shrub species extremely important. A well adapted shrub species to mitigate sagebrush loss in the native plant community is forage kochia (Kochia prostrata).

Forage kochia is a long-lived, semi-evergreen perennial subshrub native to the arid and semiarid regions of southern Eurasia. It has been seeded on thousands of acres of semiarid rangelands of the Intermountain West for reclamation, fire breaks, and wildlife and livestock forage.

Though its use can spark controversy, there is no doubt it has performed well for its intended purpose: to compete, establish and persist with invasive annuals such as cheatgrass in arid environments. Forage kochia protects sites from fires, erosion and weeds while providing a much-needed forage resource as well as structural shrub component to the plant community.

In regard to wildlife habitat, Dr. Blair Waldron, a prominent USDA-Agricultural Research Service plant material development and research geneticist referred to forage kochia as a “lifesaver” (Waldron et al. 2005). Sheepherders in central Asia call it “alfalfa of the desert” (Clements et al. 1997).

The biggest challenges that managers face using forage kochia are the timing of seed production and the ability of forage kochia seed to maintain viability beyond the initial seed production year.

Forage kochia seeds ripen in October and are often harvested October through January, though newly harvested and processed seed may not be available until after December, making seeding at the optimal time in the fall and early winter difficult with the current year’s seed availability being very limited.

There are two cultivars of forage kochia available for use, the earlier release (1986) ‘Immigrant’ (Kochia prostrata subsp. virescens) and the more recent release (2012) ‘Snowstorm’ (Kochia prostrata subsp. grisea). ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia seed can lose viability rapidly if it is not kept in cold storage. This means that seeding in the fall, at the optimal timing for success, requires using 1-year-old cold-storage seed from the previous year’s harvest or using warehouse-stored seed with lower viability and increasing the seeding rate. Both can drastically increase the cost of seeding efforts.

‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia was selected for its taller stature compared to the shorter ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia. This allows for the use by browsers in winter with ‘Snowstorm’ exposed above the snowpack.

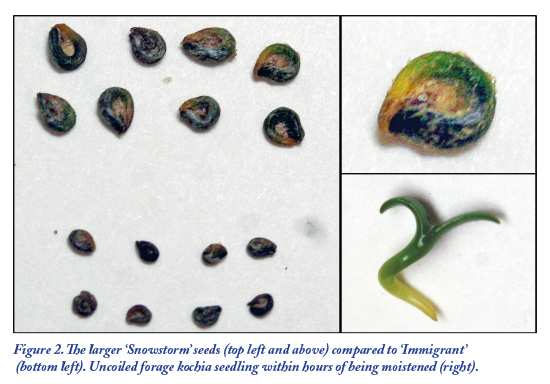

Besides the taller stature, ‘Snowstorm’ has increased nutritional value and has significantly larger seeds than ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia (Figure 2).

There is anecdotal evidence that ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia maintains seed viability longer than ‘Immigrant’, possibly relating to the larger seeds.

In an early germination publication on ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia, renowned range scientist Dr. James A. Young et al. (1981) described the unique morphology of forage kochia seeds.

The embryonic plant is tightly coiled with the cotyledons on the inside of the coil and the radicle on the outside (Figure 2).

Imagine a small seedling already formed coiled up into a round seed. The seed has a very thin membrane that allows the seedling to uncoil within hours of moistening. Unlike most seeds there is no need for the radicle to grow and emerge from the seed coat, which can take days to weeks. This rapid germination and advanced development of the seedling likely contribute to the lack of ability to maintain seed viability over time.

Often dormant seeds with thick protective seed coats can remain viable for many years. The cost of having little seed dormancy, rapid germination and no protective seed coat is a shorter time of seed viability for forage kochia. However, in highly variable arid environments, like the cold desert environments of Nevada, getting going fast is a big advantage.

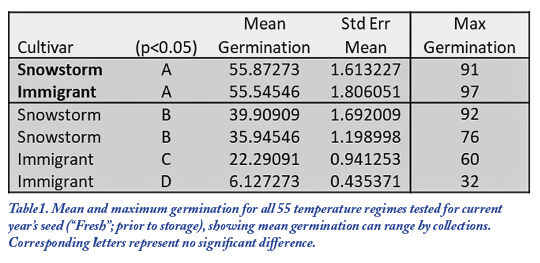

In 2018 the USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Great Basin Rangelands Research Unit, in Reno, Nevada began a study examining the viability of ‘Immigrant’ and ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia seed stored in air-tight Ziplock bags in cold storage 0°C (32°F), in typical warehouse (shed) conditions and at a constant room temperature 20°C (68°F). While 20°C is not considered “hot” it is warmer than the warehouse for most of the year and not ideal storage conditions. Seeds were harvested (November 2017) from 3 locations each for ‘Immigrant’ and ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia. Germination was tested in January 2018 for each collection (“Fresh” germination values) (Table 1). Five of the six collections were purchased from large commercial seed sellers.

One collection of ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia was grown and harvested in Reno, by the authors. We used germination as an analog for seed viability as there is typically little seed dormancy with forage kochia, leading to most viable seeds germinating. We used standardized germination test protocols developed by pioneer researchers James Young and Ray Evans (Young and Evans 1981).

Germination was tested at 55 temperature regimes that included constant and fluctuating day and nighttime temperatures representative of seedbed temperatures throughout Nevada rangelands. After 1 and 2 years of seed storage, germination (viability) was measured again for cultivar comparisons and any observations of seed viability loss.

After initial germination tests on the current years seed harvest for all six collections we concluded that there was a significant variation in seed viability among collections (Table 1).

Two of the three ‘Immigrant’ collections, which were all purchased from commercial seed sellers, had very low germination rates.

In general, ‘Snowstorm’ seed had more reliable germination among collections prior to storage. In order to make seed storage comparisons between culitvars we focused on only collections that had statistically similar seed viability to start with (Bolded in Table 1).

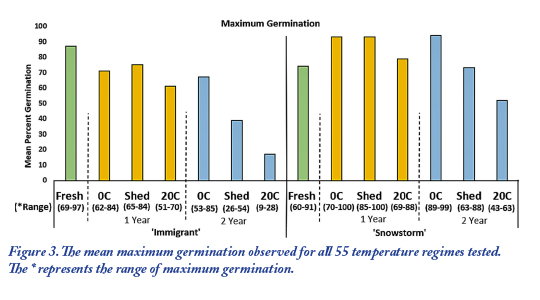

‘Immigrant’ forage kochia, as previouslyobserved, did lose viabilty after 1 year of storage in all storage conditions (Figure 3). Surprisingly, though, after 1 year, cold storage showed no improvement over warehouse (shed) storage for ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia. However, after 2 years of storage, cold storage was required to maintain seed viability for ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia.

Even more surprisingly, ‘Snowstorm’ had increased germination after 1 year in cold and warehouse storage conditions. This indicates a benefit of afterrippening time for ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia seeds.

Afterripening is complex enzymatic and biochemical process that certain seeds must undergo before they will germinate. Increased germination and decreased seed dormancy is not uncommon with many rangeland plants after a period of afterripening time.

After 2 years of storage, while cold storage did maintain a higher seed viability for ‘Snowstorm’ compared to warehouse storage, the lower-cost warehouse storage showed no decrease in germination from the initial “fresh” harvested seed.

These results have important range rehabilitation implications. Being able to use warehouse stored ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia seed at a lower cost so that seeding can be done at the optimal time in the fall will increase the chance of seeding success.

Being able to store seed and maintain viability will also improve the availability of seed for catastrophic wildfire years that require large areas to be seeded.

While the ultimate goal is to protect sagebrush habitat, forage kochia provides an affordable and reliable means to mitigate the sagebrush loss in the short-term and provide forage for grazing animals and critical browse for wildlife, especially mule deer.

Suggested Reading:

Waldron, B.L., R. D. Harrison, A. Rabbimov, T. C. Mukimov, S. Y. Yusupov, and G. Tursvnova. 2005. Forage kochia—Uzbekistan’s desert alfalfa. Rangelands, 27(1):7-12.

Clements, C. D., K. J. Gray and J. A. Young. 1997. “Forage kochia: to seed or not to seed.” Rangelands 19(4):29-31.

Young, J.A., R. A. Evans, R. Stevens and R. L. Everett. 1981. Germination of Kochia prostrata Seed 1. Agronomy Journal, 73(6):957-961.

Clements, C. D., B. L. Waldron, K. B. Jensen, D. N. Harmon and M. Jeffress. 2020. ‘Snowstorm’ Forage Kochia: A new species for rangeland rehabilitation. Rangelands, 42(1):17-21.

By Dan Harmon and Charlie Clements