The Society for Range Management-Nevada Section held its annual summer meeting on July 17, 2020. Like the rest of the world we were adapting to Covid-19 concerns and the meeting was held virtually via Zoom. We incorporated this new-world method of meeting because of our concerns for our members and the community and embraced making the best of a virtual meeting.

The Society for Range Management-Nevada Section held its annual summer meeting on July 17, 2020. Like the rest of the world we were adapting to Covid-19 concerns and the meeting was held virtually via Zoom. We incorporated this new-world method of meeting because of our concerns for our members and the community and embraced making the best of a virtual meeting.

We had already lined up a great group of presenters before the pandemic and luckily, they were more than willing to present via Zoom. While we missed the opportunity to be in the field seeing firsthand the concepts of each presentation, the expertise of the presenters and their stockpile of field photographs allowed for many real-world examples.

The theme of this year’s meeting was “Rangeland Health: Perspectives on Landscapes.” The field of range management is a multifaceted discipline encompassing many aspects of land use. From a wildlife manager to a cattle operator to the recreational enthusiast, we all share common core beliefs of rangeland health, yet each of us may interpret differently to judge the health of the range on specific values. While we may have a different perspective on the landscape based on our specific working fields, we are all connected by that landscape.

The first presenter was Keith Barker, fire ecologist with the Carson City District Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Keith conducts many projects in his district and his presentation was titled “Implementing Multiyear Large-Scale Rehabilitation Projects.” Keith began by describing the various ways the rangeland ecosystem undergoes detrimental large-scale changes. He discussed rapid changes that occur from a fire to gradual changes that occur from juniper invasion. He then described some of the methods he uses to address these changes. Some methods can be used proactively, like controlling juniper expansion through thinning operations or herbicide use to decrease annual grass fuels and creating firebreaks, or reactively, such as seeding efforts following wildfire.

Keith discussed the recent Virginia Range project north of Reno, Nevada. Approved February 2017, the project covered approximately 190,000 acres. Its main objective was to protect habitats and infrastructure by treatments to modify fire behavior. The BLM partnered with the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Geological Service (USGS), Nevada Division of Wildlife (NDOW), USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and other groups to determine the best treatments to achieve these goals. Treatments would include juniper removal, prescribed fire, seeding, and herbicide use.

As with many projects in critical habitats, the area had not yet burned in February 2017 when the project was initiated, but that would soon change. In July 2017, the Long Valley Fire burned a large portion of the project area. This changed most treatments from being proactive to reactive, but many of the tools remained the same. Because of the high density of cheatgrass pre-fire and likely increase post-fire, the use of the pre-emergent soil-active herbicide, Imazapic, was applied and fallowed for 1-year prior to seeding, in an effort to decrease cheatgrass competition and increase seeded species success.

As often occurs with BLM seeding efforts in northern Nevada, introduced species like Siberian wheatgrass and ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia were limited to their use. Introduced species seed mixes were seeded as firebreaks extending a limited distance from roads, while native seed mixes covered larger areas, often upslope with hopes the increase in elevation would provide increased seeding success. This long term effort is an ongoing project and we look forward to hearing about the results in the future.

Keith finished his presentation by showing some photos of a recent fire south of Carson City, the Numbers Fire. He showed how a firebreak treatment area, which had removed juniper fuels, helped stop the fire. This was a great example of proactive management being effective at stopping fires with fuel breaks.

The next presenter was Dr. Jeanne Chambers, senior scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her presentation was titled “What Makes Plant Communities Resistant to Nonnative Plant Invasions?” Jeanne first explained what a plant specie’s fundamental niche and realized niche are and how they affect nonnative plant invasions. A species fundamental niche is determined by the environment, climate, topography and soil type. The realized niche is determined by the species composition of the existing plant community. These two, combined, can determine the likelihood of nonnative invasion.

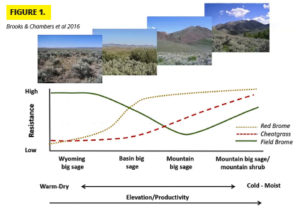

Dr. Chambers then described how our sagebrush communities exist over a wide range of environmental gradients, giving them various degrees of resistance to invasions of nonnatives such as cheatgrass (Figure 1).

Dr. Chambers then described how our sagebrush communities exist over a wide range of environmental gradients, giving them various degrees of resistance to invasions of nonnatives such as cheatgrass (Figure 1).

Wyoming big sagebrush habitats, which are at lower elevations and exhibit warmer and dryer conditions, therefore support lower densities of perennial grasses and forbs and are less resistant to cheatgrass invasion. Mountain big sagebrush sites which are higher elevation and experience cooler and wetter conditions and thus support higher densities of perennial grasses and forbs, are more resistant to cheatgrass invasion. To further simplify, higher densities of perennial grass equal greater resistance to cheatgrass invasion. This is the framework for fuel breaks that Keith Barker discussed, where the aim is to establish a high density of perennial grass to keep out cheatgrass and associated fuels that would carry a fire. Jeanne described mechanisms that perennial grasses use to resist cheatgrass invasion.

By sharing the same soil root zone as cheatgrass, the perennial grass can deplete the water and nutrient resource pool, thus limiting the establishment and growth of the annual invader. Jeanne determined through experimental and observation comparisons of perennial herbs that about 20% perennial herbaceous cover is required to resist increases in cheatgrass. She finished her presentation with a discussion of the tenuous balance between grasses, shrubs and annual invaders. If shrub density gets too high, the shrubs can outcompete the perennial grasses and decrease the cheatgrass resistance, and thus increase wildfire threats. Best grazing management practices are of critical importance to maintain a healthy, diverse balance of shrubs, perennial grasses and low annual grass cover. Postfire rehabilitation that maintains or establishes the required perennial grass cover is also of critical importance.

The next presenter was Gabe Ludwig, a representative with Bayer Environmental Sciences. His presentation was titled “Rejuvra® A Newly Registered Herbicide for Annual Grass Control in Rangelands.” The active ingredient in Rejuvra, Indaziflam, is also the ingredient in EsplAnade™ 200SC, which is registered for areas that are not to be grazed. With the grazing approval for Rejuvra the opportunities for annual grass control on rangelands is greatly increased, he said.

Gabe explained how the use of a pre-emergent herbicide like Rejuvra which controls the annuals while having no negative effect on established perennial plants can help to break the invasive annual grass fire cycle. Not only is the annual grass controlled but the existing perennial grasses are often “released,” increasing their vigor and period of greenness and decreasing the chance and season of wildfire. By removing the annual grasses, the soil resources and moisture they would use can now be used by perennial grasses. He noted that while previously used pre-emergent herbicides such as Imazapic provide about 1-year growing season of control, Rejuvra has been observed to provide up to 4-years growing seasons of new seedling control. This is likely to be highly variable based on the environment which the herbicide is used but provides promising longer-term control. This may provide a great management opportunity in those areas where the perennial grass cover falls just short of the 18% cover that Dr. Chambers determined is required for cheatgrass resistance.

By controlling the annual grasses in those plant communities and releasing the perennial grass component, fire threats will decrease. Multi-year control can also further deplete the persistent cheatgrass seed bank which is critical for long-term cheatgrass management. As with other pre-emergent herbicides, such as Imazapic, application timing is critical and needs to occur in early fall prior to any germination events. For now, the BLM process for approved use of Rejuvra on Nevada BLM rangelands hasn’t begun, but hopefully as more benefits are demonstrated approval can proceed.

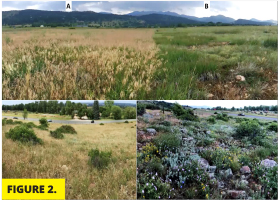

Presenting next was Shannon Clark, a faculty affiliate with Colorado State University and a contractor for Bayer, Western Stewardship and Development. Her presentation was titled “Promoting Native Forb Habitat While Reducing Wildfire Risk.” Shannon first discussed the threat that annual invasive grasses pose to pollinator habitats on the Colorado Front Range. Like Gabe Ludwig’s discussion of releasing perennial grasses by controlling annual grasses, Shannon presented examples of increasing perennial forb presence by controlling annual grasses using Rejuvra (Figure 2).

Presenting next was Shannon Clark, a faculty affiliate with Colorado State University and a contractor for Bayer, Western Stewardship and Development. Her presentation was titled “Promoting Native Forb Habitat While Reducing Wildfire Risk.” Shannon first discussed the threat that annual invasive grasses pose to pollinator habitats on the Colorado Front Range. Like Gabe Ludwig’s discussion of releasing perennial grasses by controlling annual grasses, Shannon presented examples of increasing perennial forb presence by controlling annual grasses using Rejuvra (Figure 2).

Shannon’s research found increases in flower production, cover percent and richness of forbs, and 2.5 times more rare species in herbicide treated vs. untreated areas, likely due to annual grasses outcompeting these forbs. Shannon discussed how increases in forb richness facilitate pollinator diversity, and how controlling annual grasses with Rejuvra® decreased the wildfire threat. At Shannon’s study area, cheatgrass litter or fuel decreased from 900 lbs./acre to less than 100 lbs./acre on herbicide treated plots.

Last, Shannon gave an example of a study using Rejuvra to control annual grasses in Wyoming where a wildfire unexpectedly started during the study and burned around the study area. She showed photos where the fire was unable to burn through the herbicide treated plots, presumably from the lack of annul grass fuels and the increase in green perennial grass cover. This was another great real-world example of these treatments, like Keith Barker’s example of fire breaks being successful at controlling wildfires.

Both Shannon and Keith’s examples of effective fuels management are proactive efforts, but we know fires are going to happen, so we also need effective post-fire treatments.

Our last presenter, Mark Freese with the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW), focused on effective post-fire rehabilitation treatments. Mark is the Western Regional Habitat Biologist for NDOW and heads an impressive team that, in cooperation with public (BLM and Forest Service) and private landowners, seeds tens of thousands of rangeland habitat annually. His photographic records of the outcomes of these projects as they relate to different seed mixes, rates, application timings and methods is a valuable bank of knowledge.

Mark began by emphasizing what Dr. Chambers and others had discussed, that deep rooted perennial bunchgrasses are the primary factor to suppress cheatgrass and decrease wildfire threats. He stressed that this narrow focus on one functional group does not limit the importance of plant community diversity or the ability to manage for plant diversity which is critical for wildlife populations. Plant diversity is most achievable when resistance to annual grass invasion and decreased wildfire threats occur, which relies on maintaining perennial grass cover.

Mark discussed how he defines a successful seeding effort, which can be subjective, based on the goals of the effort. He stated that in general, NDOW’s goal is to facilitate plant community improvements with herbicide use and seeding efforts that can further improve through passive management efforts. He described the multiple methods of seed acquisition NDOW use to purchase large quantities of seed each year and the importance of getting the seed early enough to have seeding efforts occur before the winter season (before January). Unlike the BLM they do not have the limitations of native vs. nonnative seed use.

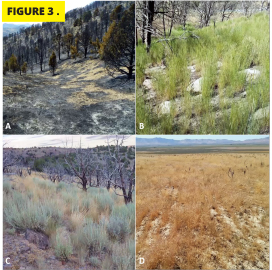

Mark explained they focus on plant functional groups and the service they provide to wildlife as opposed to focusing on specific species. Mark gave many examples of his projects with success, failures and missed opportunities (Figure 3).

Mark explained they focus on plant functional groups and the service they provide to wildlife as opposed to focusing on specific species. Mark gave many examples of his projects with success, failures and missed opportunities (Figure 3).

Mark discussed the concept of hedge betting seed mixes, where introduced plants such as Siberian wheatgrass and especially ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia are added to primarily native seed mixes, so that if low precipitation or high cheatgrass competition occurs, the introduced plants can provide some degree of successful establishment. Using animal fecal pellet counts, they found magnitudes greater wildlife use where ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia established.

Mark’s take-home message was “doing nothing and limiting yourself is a choice,” but let’s take some risks and do more on the landscape using the best science and past experiences, hedge our bets and use the best timing practices to have a positive impact on the health of our rangelands. To view the full presentations please visit Nevada.Rangelands.org.

By Dan Harmon and Dave Voth