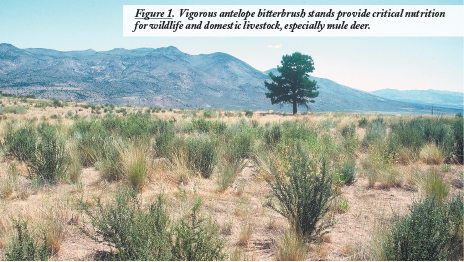

Purshia species, such as antelope bitterbrush, are very important in the nutritional demand of mule deer, and to a lesser degree, domestic livestock. In order to appreciate the nutritional aspects of antelope bitterbrush, some understanding of the unique nutritional requirements of mule deer, the primary consumer of antelope bitterbrush browse is necessary (Fig. 1).

Purshia species, such as antelope bitterbrush, are very important in the nutritional demand of mule deer, and to a lesser degree, domestic livestock. In order to appreciate the nutritional aspects of antelope bitterbrush, some understanding of the unique nutritional requirements of mule deer, the primary consumer of antelope bitterbrush browse is necessary (Fig. 1).

Analysis of forage samples are among the first scientific tests applied by resource managers attempting to better understand the role of forage plants in the ecology of western rangelands. Most analysis focused on grasses rather than shrubs since the objective was to better understand the forage requirements of domestic livestock rather than mule deer. By the late 1930s, wildlife ecologists were making serious attempts to better understand the nutritional requirements of mule deer. Wildlife ecologists, L. A. Stoddard and J. E Greeves reported on their attempt to conduct forage analysis of grasses shrubs and forbs on mule deer summer ranges in Utah. Noting that their forage analysis occurred on summer range habitat rather than mule deer winter ranges, they noted that antelope bitterbrush had a crude protein content of 15.4%, and therefor concluded that antelope bitterbrush is a highly reliable source of browse. Crude protein is often considered the most important dietary nutrient, as ungulates cannot survive without it. Even a slight deficiency adversely affects reproduction, lactation, and growth. Ruminants need protein in order for the rumen microorganisms to digest and metabolize carbohydrates and fats effectively. The nutrient, usually reported as crude protein, is a measure of protein and nonprotein nitrogen. The amount of nitrogen compounds present in various vegetation classes varies with the kind of tissue, age or stage of development, and the time of season. In general, shrubs like antelope bitterbrush contain higher percentages of crude protein than do grasses and forbs during the fall and winter months, yet lesser amounts during the spring and summer months. It is not uncommon to have a rancher gathering cattle in the fall to find his stock in an antelope bitterbrush stand due to the preference for digestible crude protein.

Most of the plant material eaten by mule deer and other ruminants consists of some form of carbohydrates, which provide most of the energy needed in the diet. Fats, lipid and related substances are frequently reported in nutritional analysis as crude fat. True lips are simple lips, true fats and oils, compound lipids, and derived lipids such as saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Most of these are digestible to some degree by ruminants, but some of the other soluble compounds such as terpenes and resins, are not digestible and may be harmful to rumen function, which we will touch on later.

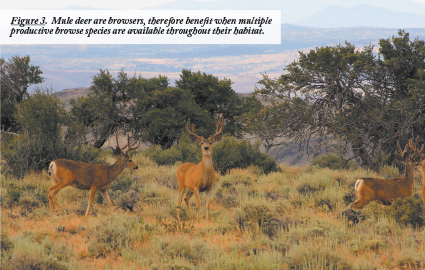

Fats are a highly important food reserve in animals because they contain almost twice as much energy per unit weight as carbohydrates and protein. While the fat content of dry fruits and seeds of shrubs may be as high as 70%, lipids rarely make up 5% of the stem and leaf constituents. Fats are synthesized in the rumen from carbohydrates and proteins, therefore ruminants such as mule deer do not require fats in their diet, but wintering animals prefer and do well on diets consisting of shrubs such as winterfat, mountain mahogany and antelope bitterbrush. Rocky Mountain juniper tests high for crude fat but is high in essential oils that interfere with rumen function. Secondary compounds of terpenes are also present in big sagebrush, and as reported by animal nutritionist D. R. Diets, when mule deer consume 55% or more big sagebrush in their diet, the high levels of volatile oils can significantly harm rumen function and result in mortality. That is why it is so important to have diverse shrub communities in which mule deer can browse multiple shrub species and benefit from the nutritional value big sagebrush provides, without consuming toxic levels of volatile oils (Fig. 2).

Ruminants, such as mule deer, must have access to adequate calcium and phosphorus. Calcium and phosphorus compounds form 90% of the mineral matter in the skeleton of most ruminants and about 75% of that in the entire body. On western rangelands, calcium supplies are usually ample in shrubs. Phosphorus is vital in many body processes including skeleton strength, intracellular fluids and compounds such as nucleoproteins and phospholipids. A deficiency in phosphorus or a high calcium to phosphorus ration may result in weak young (fawns), decreased lactation, failure to conceive and other abnormalities. Phosphorus is deficient in many shrub species on western rangelands during the winter months. Most ruminant nutrient intake goes towards maintaining its general metabolism. Browse species such as antelope bitterbrush, mountain mahogany and big sagebrush are good sources of energy, but as shrubs become older their nutritional value decreases as well.

Much of what is known about the nutrition of mule deer comes from the pioneering research of Arthur D. Smith, a long-time professor at Utah State University who worked in cooperation with the Utah Fish and Game Commission. One of the first papers Smith published on mule deer nutrition concerned the digestibility of big sagebrush. Based on field observation he reported that mule deer commonly consumed big sagebrush herbage and on winter ranges big sagebrush consumption increased, especially when more desirable species such as antelope bitterbrush were not available. Wildlife biologist, Harold Bissel and his associates in the California Department of Fish and Game conducted digestibility trials of antelope bitterbrush and big sagebrush in northeastern California in the mid-1950s. Bissel reported good intake of antelope bitterbrush by mule deer, but when compared to big sagebrush, mule deer could not maintain body weight. Bissel calculated the energy requirements from his experiments and reported that mule deer consumed about 4,500 calories per 100 pounds of body weight, the maintenance requirement of a resting and fasting mule deer was 1,140 calories per day/100 pounds of body weight. Bissel reported that antelope bitterbrush could maintain body weight as a sole source of forage, which was not the case with big sagebrush.

Wildlife biologist, R. W. Lassen obtained similar results on the nutritional importance of antelope bitterbrush to mule deer in northeastern California with the Doyle mule deer herd. Lassen’s team analyzed 213 mule deer stomachs during the winter of 1949-1950 and reported that the primary browse was big sagebrush, however they noted that the mule deer they examined (natural death and road kill) were in very poor condition. By April they reported that 30% of the deer they examined exhibited signs of advanced malnutrition with the herbaceous species most frequently found in the diets of mule deer to be alfalfa and cheatgrass. They reported that grass made up 56% of the mule deer diet from November 1949 through March 1950. Once antelope bitterbrush began its growth in April, grass declined to 5% of the diet.

Other studies by Bissel, with the aid of California Department of Fish and Game wildlife biologist Howard leach, reported that antelope bitterbrush was preferred from September through November in the diet of the Lassen-Washoe mule deer herd, by December antelope bitterbrush and big sagebrush consumption by mule deer was nearly equal and big sagebrush increased to greater portions of the diet than antelope bitterbrush in February and March. It is important to remember that during this time period in northeastern California, antelope bitterbrush was the keystone browse species and inherent bias may have played a role in the overall reporting.

Howard Leach, whom analyzed more than 3,000 mule deer stomachs reported to us that mule deer in northeastern California preferred antelope bitterbrush from September to mid-December and that the availability of vigorous antelope bitterbrush stands was critical in allowing mule deer to obtain the nutritional values of antelope bitterbrush as they make their way to winter ranges. He reported that even though the preference for big sagebrush increased from December through March, the worst condition the mule deer was in coming into winter range habitat, the more mortality the deer herd would experience. “Foods of Rocky Mountain Mule Deer” that was published back in 1973 had already listed 52 publications referring to the foraging of mule deer on antelope bitterbrush. Nonetheless, mule deer are not the only browsers that consume antelope bitterbrush. Bighorn sheep, elk, moose and pronghorn antelope also utilize the nutritional value that antelope bitterbrush provides. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks reported, in research they funded, that antelope bitterbrush made up more than 50% of the mule deer diet. In their report they pointed out the significant increases in Elk populations and that antelope bitterbrush nutritional value was preferred by elk as well, resulting in habitat competition. Even though the elk diet was more diverse, major browse species that made up 95% of mule deer diets also made up 55% of elk diets.

In southcentral Wyoming, antelope bitterbrush made up 80-90% of pronghorn and mule deer summer and fall diets, suggesting yet another sign of resource competition for antelope bitterbrush.

In western Colorado, Range Scientist R. M. Hansen reported that Utah serviceberry and antelope bitterbrush made up 96% of mule deer summer, fall and early winter diets. Hansen also reported that with an increase in nutritional browse species such as antelope bitterbrush, mule deer could utilize the nutritional value of pinyon and juniper and offset rumen complications of volatile oils associated with these two tree species.

Preference of forage species is often related to abundance, but can also be due to the plants volatile oils as discussed with big sagebrush and pinyon or juniper trees which can be recognizable by smell or taste. Again, the more availability of vigorous browse species such as antelope bitterbrush, serviceberry and mountain mahogany the more that browsers such as mule deer can utilize nutritional browse species with volatile oils that can harm rumen function (Fig. 3).

Habitat changes over-time have resulted in a decrease in shrub communities, including antelope bitterbrush, which have resulted in former big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities being converted to annual grass dominance, cheatgrass, therefore increasing the chance, rate, spread and season of wildfires that in return threatens critical unburned browse communities. Also, many browse communities are becoming old and decadent and providing less nutritional value for wildlife, especially mule deer.

We have reported on the age of antelope bitterbrush stands that are well over 70 years of age. Once antelope bitterbrush plants reach 60-70 years of age they start to decline in nutritional value, leader growth, seed production and recruitment ability.

We reported that antelope bitterbrush shrubs that average 30-40 years of age produced an average of more than 90,000 seeds per shrub compared to shrubs that average 90-100 years of age producing less than 900 seeds per shrub.

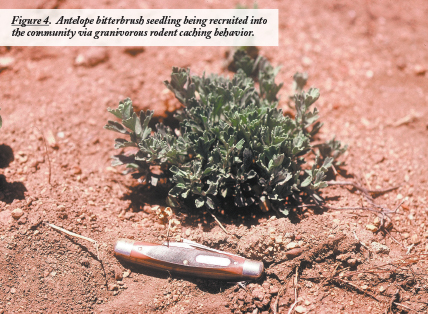

Granivorous rodents are the primary dispersal mechanism of antelope bitterbrush seed. Granivorous rodents exhibit two types of dispersal behavior: larder hoarding is the behavior in which they harvest the seed and take the seed deep within their burrows, these seeds may germinate, but are not available for emergence and establishment. Their other behavior is scatter hoarding, this is where they harvest the seed and disperse the seed in shallow depressions throughout their home range. Rodents harvest approximately 98% of the bitterbrush seed that falls to the ground and consume about 76% of those seeds. Roughly 52% of the bitterbrush seed that was produced on the plants were damaged by insects or frost. Therefore, the more seed production, the more scatter hoard caches, the more opportunity for seedling emergence and establishment to be recruited into the community.

The recruitment of new plants is critical in sustaining any plant community, but with the exceptional preference for antelope bitterbrush, this important browse species relies even more heavily on sustaining vigorous nutritional forage for mule deer, other wildlife species and domestic livestock for many decades (Fig. 4). Therefore, the restoration of antelope bitterbrush throughout its’ range is critically important to numerous habitats and the wildlife and domestic livestock that depend on these habitats, especially mule deer.

By Charlie D. Clements and James A. Young, Rangeland Scientists, USDA-ARS, Great Basin Rangelands Research Unit