PART 3 OF 3

This is the final part of a three-part series addressing the importance of management in improving mule deer population densities and their habitat.

Mule deer are native to North America and are the primary big game species in Nevada and other western states. Mule deer are a valuable economic resource for State, County and local communities through their recreational opportunities.

Management of mule deer is critical to provide and continue recreational and hunting opportunities which requires the understanding of population dynamics driven by a complexity of biotic and abiotic factors such as climate, fire, habitat conditions, predation and highway vehicle collisions. Wildlife managers are tasked with the complexity of these factors that are continually changing and intermixing with each other.

According to numerous researchers, habitat quality is the number one driving force behind increases and decreases in mule deer populations.

The use of radio-collaring mule deer herds is critical in identifying summer, transitional and winter ranges. Following this identification, it is then possible to quantify the condition of these habitats and address limiting factors such as stand decadence (older less nutritious browse species), loss of habitat due to wildfires, Pinyon-juniper encroachments, and migratory issues.

The better quality and nutrition of the plant species the healthier condition the animals are to conceive, produce and recruit fawns back into the population (Figure 1) as well as reduce predation, disease and winter mortality.

Amount and periodicity of precipitation is the main driving force behind a plants ability to provide nutrition, flower, produce seed and recruit seedlings back into the environment.

Being that Nevada is the driest State in the Union, the State receives more dry years that wet years, thus we have average precipitation zones that may only receive the average or above average precipitation about 40% of the time.

The cold desert of the Great Basin receives the majority of its precipitation during the winter months in the form of snow which results in increased soil moisture for the coming spring, but periodicity of spring and summer precipitation are critical in continued nutritional value as well as recruitment of seedlings of desirable species.

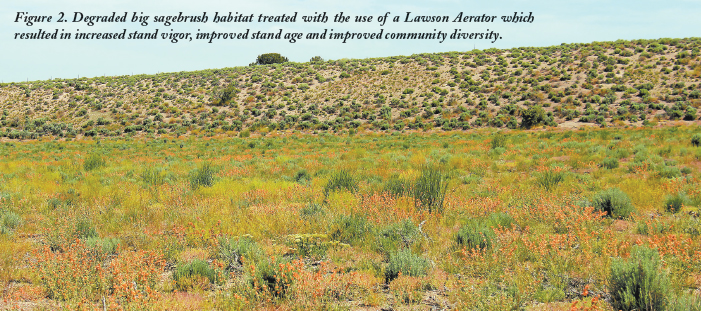

Once habitat limitations are identified, the challenges begin. In the case of stand decadence, depending on the potential of the plant community, deliberate manipulation of habitats will need to be conducted to improve stand vigor (Figure 2).

The higher elevations that receive more favorable precipitation respond very well to disturbances that set back succession, add edge effect and improve the stand age of perennial grasses, forbs and shrubs. One of the problems with these higher potential habitats, mountain brush communities, is that they account for a smaller percentage of the overall mule deer habitat.

Wyoming big sagebrush/bunchgrass habitat types make up more than 50% of Great Basin rangelands followed by nearly 30% of very arid salt desert shrub communities.

Wyoming big sagebrush/bunchgrass habitat types add significant risks when attempting plant manipulation due to the presence of cheatgrass in the environment and the seed bank.

Cheatgrass has the ability to build persistent seed banks that can last 3-5 years, thus following the disturbance cheatgrass becomes the vacuum plant as seedlings of this invasive annual grass outcompete perennial seedlings for limited resources to survive and establish. Nonetheless, if you do nothing the odds are the site is going to burn sooner than later and most likely under uncontrollable situations.

Not only is the old decadent browse species not providing quality nutrition and reproductive ability, these stands increase the intensity of wildfires. Antelope bitterbrush for example, has a very low percentage of resprout ability following wildfire, about 3%, and once the plant reaches around 60 years of age it starts to decline significantly in its overall condition. There are antelope bitterbrush stands that are near or over 100 years of age with no to minimal recruitment and provide little value other than cover and minimal nutrition. These older shrubs have a significant reduction in leader growth that results in less forage, decreased palatability and nutrition and an increase in volatile oils that can be harmful to mule deer. Pinyon-juniper encroachment also requires deliberate manipulation as these pinyon-juniper stands crowd out grasses, forbs and shrubs and decrease the overall ability of these communities to support mule deer.

More than 40% of the moisture these habitats receive never makes it to the ground due to the canopy cover and evaporation resulting in decreased spring flow that effects the entire watershed. Manipulation of these stands through chaining, lopping, cut and removal, mastication, etc. can result in a significant release of residual desirable vegetation with increased vigor and nutrition that are very beneficial to not just mule deer, but numerous other wildlife species.

Wildfires have significantly impacted habitats throughout the Great Basin, especially browse communities that mule deer rely on for their very survival. Millions of acres of big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities have been converted to annual grass dominance. The ability of resource managers to aggressively and effectively restore or rehabilitate rangelands burned in wildfires is a monumental task.

Cheatgrass invasion and climate realities make it very difficult to successfully restore and/or rehabilitate these degraded habitats, nonetheless, extensive efforts and measurable successes give light to future endeavors.

Resource managers have become more aggressive in these efforts using proper seed mixes and methodologies as well as pre-emergent herbicides to control cheatgrass densities and aid in the establishment of desirable perennial species.

The use of non-native plant materials such as crested wheatgrass and Siberian wheatgrass have provided resource managers with aggressive perennial grasses that are needed to suppress cheatgrass densities and associated fuels which decreases the chance, rate, spread and season of wildfires. The use of forage kochia has provided mule deer with much needed nutrition when the seeding of native shrubs has experienced high failure rates. The use of forage kochia has minimized winter mortality significantly, although the percentage of the landscape treated with this species is less than 1%.

Forage kochia seedings performed in the 1990s and thereafter are highly preferred by mule deer and provide critical nutrition to migrating and wintering mule deer herds today, all because of the recognition of this species as a beneficial browse species that could be successfully seeded on arid Great Basin rangelands.

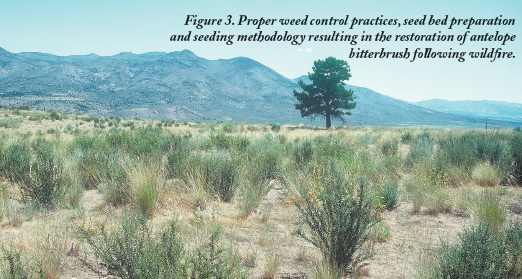

The continued efforts of researchers and resource managers to test weed control practices, plant materials, seeding methodologies, and transplanting opportunities are going to be very important in any attempt to restore and rehabilitate mule deer habitats (Figure 3).

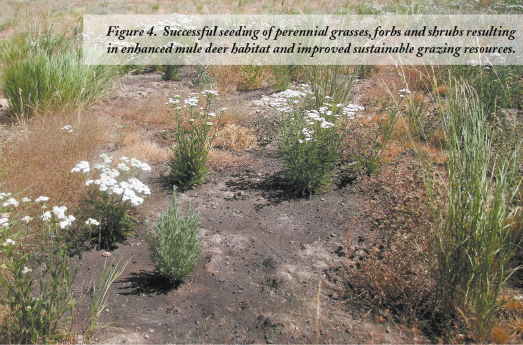

An important component of proper restoration/rehabilitation practices is the value of proper grazing management. Improper grazing management can lead to excessive grazing of seedlings of seeded species reducing the overall level of success of restoration/rehabilitation projects.

It is hard enough to get survivability of seeded species in these arid Great Basin environments, let alone over graze following such extensive efforts. Understanding the level of success and health of seeded species will allow resource managers and livestock operators to monitor the site and achieve goals such as mule deer habitat restoration and sustainable grazing practices (Figure 4).

The maturity of these successful seedings may be slower than anticipated, therefore management decisions will have to be made to make an effort to allow these seedings to come to a maturity level that is more resistant to livestock grazing pressure. On the other hand, if a seeding effort fails, it is not a good idea to rest the site and hope some miracle happens, as all this will do is result in an increase in cheatgrass and associated fuels which increases the threat of wildfires which threatens adjacent unburned habitats.

The better the habitat conditions, the less negative affect that predation will have on these already struggling mule deer herds. Predation can affect mule deer population if it is at least partially additive to mortality from other causes such as habitat loss, extreme winter conditions and urbanizations. Researchers have reported that predators do not cause declines in mule deer populations in undisturbed habitats, but may prevent or delay mule deer population recovery after a decline. This point should be well taken given the fact that much of the transitional and wintering mule deer habitats in the Great Basin are disturbed. Even though as little as a 6% predation rate on mule deer is reported to not significantly impact mule deer herds, the accumulative predator pressure over decades in association with other limiting factors can most certainly have a negative impact on mule deer populations and recovery. It is important to maintain mule deer migration corridors and pathways for future mule deer movements given the current benefits of migration to annual doe and fawn survival. Conservation easements, highway over and underpasses and highway signage can all significantly decrease mule deer mortality during migration periods. It is not uncommon to have more mule deer killed by highway accidents than the annual harvest of that specific herd. Highway road signs alone are reported to decrease highway mule deer mortality by more than 50%. Agricultural areas, such as alfalfa fields are quite the magnet to mule deer in certain habitats. Fawn mortality can be significant as a newer generation of swathers cut the crop at speeds that exceed 10mph versus the previous 3-4mph speeds. Bob Hoenck, of the Hoenck Ranch in western Nevada, recognized this reality and therefore sends riders out through his fields before the swathers enter to reduce fawn mortality. These are just examples of a multi-prong approach to improving mule deer habitat, reduce mortality outside of responsible harvest limits, which combined can play an important role in increasing mule deer populations.

The management of mule deer and their habitat is complex as numerous factors play a role in the health, or lack of, of mule deer herds throughout the Great Basin. Understanding that many factors are associated with the health of mule deer herds should be understood and addressed. Improving habitat conditions of summer, transitional and winter ranges can increase fawn production, decrease breeding female mortality, decrease winter mortality, decrease predation, and increase carrying capacity. The efforts put forth today are critical if our future mule deer herds are to have suitable habitat that will be in demand in the near future as well as decades down the road. Habitat conditions though are not the only piece of the pie.

Urbanization, agricultural practices, predation, and migratory constraints such as highways can all lead to added mortality of mule deer herds and their ability to produce healthy mule deer populations. Engaging in this important topic and addressing all the pieces of the pie will result in improved mule deer populations, which is good for wildlife and agricultural practices alike.

By Charlie D. Clements