The Western U.S. is no stranger to extreme drought. It’s been several generations, though, since farmers’ and ranchers’ ability to produce food and fiber have been hampered to this degree by dry conditions. Crop acreage reductions, orchard tree removals and livestock herd liquidations have been common responses from farms and ranches facing drought. In the Colorado River Basin, which covers over 246,000 square miles and provides vital water resources to Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and northern Mexico, the largest reservoirs have reached their lowest water levels in history. Under the Colorado River Basin guidelines, low reservoir levels have triggered the first shortage declaration in history and with it a range of water allocation curtailments.

The Western U.S. is no stranger to extreme drought. It’s been several generations, though, since farmers’ and ranchers’ ability to produce food and fiber have been hampered to this degree by dry conditions. Crop acreage reductions, orchard tree removals and livestock herd liquidations have been common responses from farms and ranches facing drought. In the Colorado River Basin, which covers over 246,000 square miles and provides vital water resources to Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and northern Mexico, the largest reservoirs have reached their lowest water levels in history. Under the Colorado River Basin guidelines, low reservoir levels have triggered the first shortage declaration in history and with it a range of water allocation curtailments.

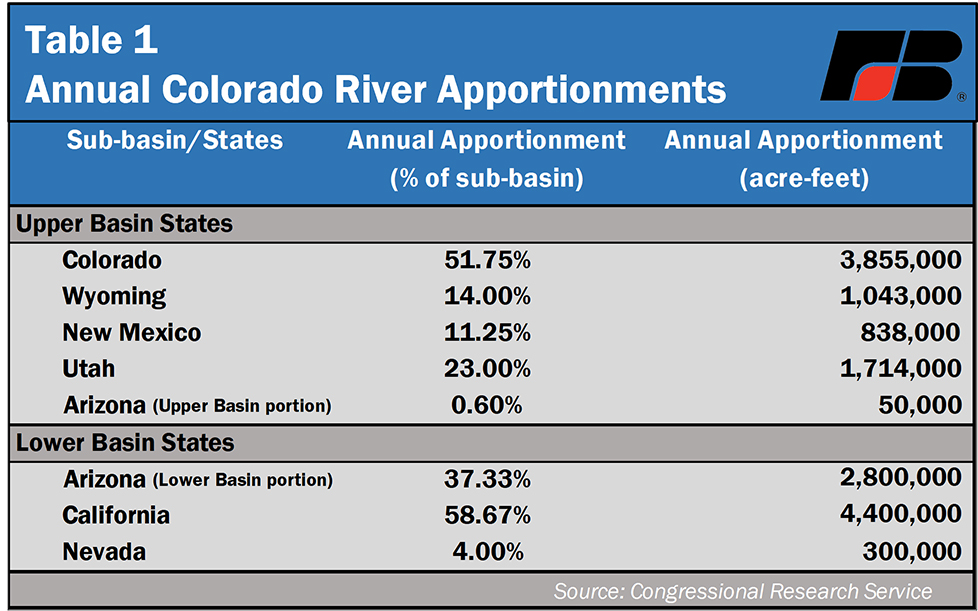

The Colorado River Basin is a primary source for farm and rangeland irrigation across 5.5 million acres of land and is also used for municipal and industrial purposes by the region’s 40 million-plus residents. The region’s hydroelectric infrastructure provides up to 42 gigawatts of electrical power annually to area customers. As a result of the Colorado River Compact of 1922, the basin was split into two separate water apportionment regions, the Upper Basin, which covers Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and a small section of Arizona, and the Lower Basin, which covers the majority of Arizona and provides water to populated sections of Southern California and Nevada. Under the compact, each basin is allocated 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) yearly, with an additional 1.5 maf dedicated to Mexico.

The Bureau of Reclamation, a federal agency within the Department of the Interior, oversees water resource management including the delivery, diversion and storage of Colorado River Basin water flows. The bureau monitors conditions, such as inflow, water storage capabilities, elevation and evaporation, and manages total releases from the basin’s numerous reservoirs, with a particular focus on the two largest reservoirs: Lake Powell on the southern border of Utah (created by Glen Canyon Dam) and Lake Mead on the border of Nevada and Arizona (created by Hoover Dam). Multi-year drought has impacted the level of Rocky Mountain snowpack, which the Colorado River relies on for its flows. Reduced inflow from snowpack results in reduced reservoir levels and a reduction in the amount of water available for downstream users especially as population and associated water demand increases. A Reclamation study estimated 64-76% of consumption demand growth was expected to come from municipal and industrial use by the area’s growing population, rather than from increased agricultural demand.

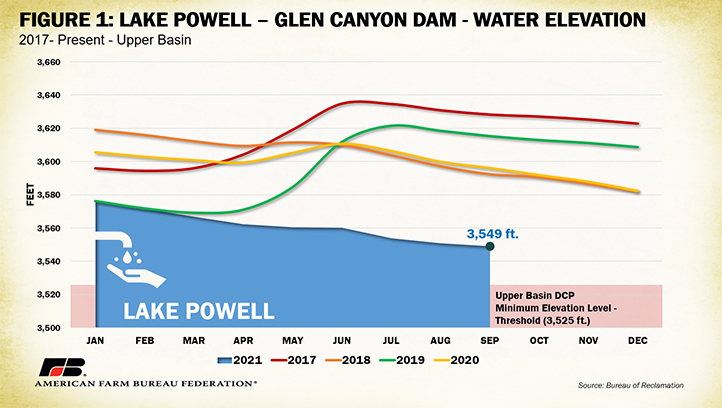

In an effort to avoid future water shortage disasters and improve storage decisions, the Upper and Lower Basin states worked collaboratively with Reclamation to agree to and implement a series of water shortage mitigation procedures called the Drought Contingency Plans (DCPs), which were approved by Congress in 2019. For the Upper Basin, states agreed to the operation of regional units to keep the elevation of Lake Powell above 3,525 feet (35 feet above the minimum needed to support hydroelectric production). This goal would be achieved through drawdowns of other Upper Basin water storage facilities and voluntary buyer agreements for paid water use reductions. Figure 1 shows the elevation of Lake Powell from 2017-present. To date, Upper Basin states have been successful at preventing Lake Powell’s elevation from dropping below 3,525 feet. That said, the reservoir is still at its lowest recorded level, reaching 32% of its 24.3 maf max capacity (compare to 48% of capacity in September 2020).

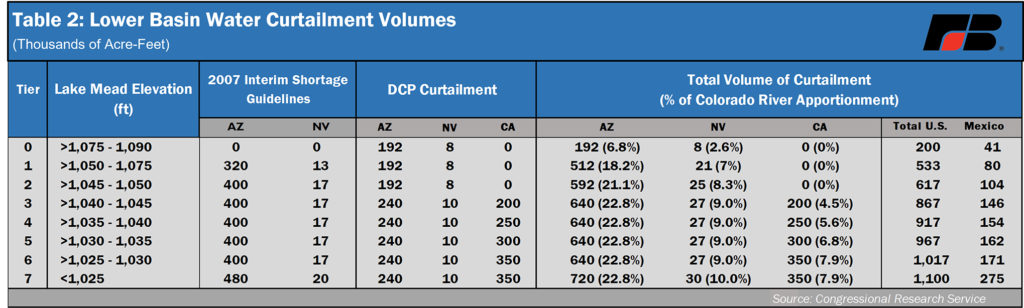

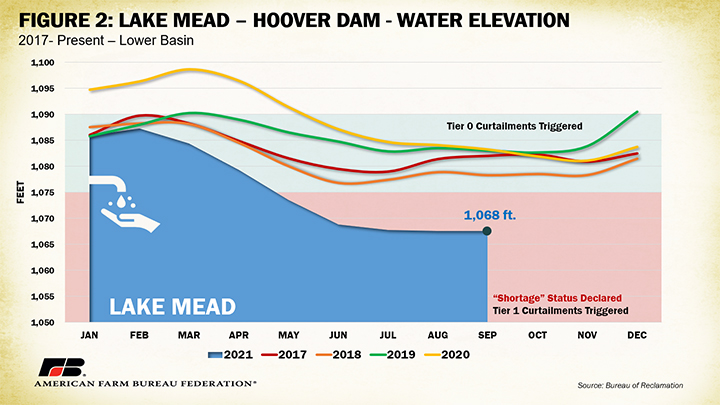

In the Lower Basin, Arizona, California and Nevada reservoir usage is governed by a more complex framework, and the secretary of the Interior is the watermaster of the lower Colorado River, giving the federal government a significant role in water management. In 2007, the region adopted a series of mitigation procedures known as the Colorado River Interim Guidelines. Based on Lake Mead elevation level triggers, the 2007 guidelines called for progressively greater cuts as lake levels fall below 1,075 feet. Another feature of the guidelines is intentionally created surplus water, which is created when states invest in conservation to reduce their deliveries and increase storage at Lake Mead for future years. The Lower Basin DCPs establish additional trigger levels and curtailments for reservoirs in the area.

Table 2 displays the volume reduction requirements by state and governing policy.

Until recently, Arizona and Nevada were operating under the Tier 0 level of the DCP requirements, reducing their total apportionments by 6.8% and 2.6%, respectively. Lake Mead elevations between 1,090 and 1,075 feet are not categorized as a shortage, making these preliminary curtailments a protective buffer from further drops. Unfortunately, with persisting drought conditions, Lake Mead recently dropped below the 1,075-foot threshold, warranting the first declared shortage in history from the Department of the Interior. Figure 2 shows the elevation of Lake Mead from 2017-present. As of Sept. 1, Lake Mead was reported at 35% of its 26.1 maf max capacity (compare to 40% of capacity in August and September 2020).

The shortage declaration will trigger Tier 1 curtailments under DCP and Interim Guideline requirements in the 2022 water year, which begins Oct. 1, 2021. Arizona will be most impacted because of its junior water rights, losing 18% of its annual allocation, or 512,000 acre-feet of water, which translates to 8% of the state’s water use. Additionally, Nevada will lose approximately 7% of its allocation, or 21,000 acre-feet of water, while California remains spared due to its water rights seniority advantage. Any cuts will likely impact agricultural use first as municipal use receives preference.

Conclusion

The Department of the Interior declared the first-ever Colorado River Basin water shortage on August 16. Arizona and Nevada, which combined generate nearly $6 billion in agricultural receipts, will be directly impacted by additional cuts to water allocation. Continued drought conditions risk additional cuts across the Colorado River Basin, jeopardizing thousands more farm and ranch operations’ access to vital water resources. Moving forward, drought mitigation approaches must consider the crucial role Western agriculture plays in a secure domestic food supply.

Contact: Daniel Munch | Associate Economist

(202) 406-3669 | dmunch@fb.org

FARM BUREAU: fb.org