It is well documented how difficult of a task resource managers have when attempting to restore or rehabilitate disturbed or degraded habitats throughout the Great Basin. These challenges are multiplied many times over when attempting to restore or rehabilitate severely arid habitats.

It is well documented how difficult of a task resource managers have when attempting to restore or rehabilitate disturbed or degraded habitats throughout the Great Basin. These challenges are multiplied many times over when attempting to restore or rehabilitate severely arid habitats.

Rangeland revegetation has been around for more than a century and many experienced researchers have cautioned future researchers on the numerous challenges that lay ahead when addressing the restoration or rehabilitation of range sites that are not only degraded but are also severely limited by lack of effective amount and periodicity of annual precipitation. Sites that regularly receive less than 7” of annual precipitation often lack the necessary precipitation to achieve any level of revegetation success.

Researchers have reported that favorable conditions to establish seeded plants in these arid environments may only occur 1 out of every 4 years, while others have reported the necessary conditions needed to recruit natural or artificially induced seedling recruitment vegetation may only occur 1 or 2 years out of every 15 years. Nonetheless, many of these habitats are critical to wildlife as well as sustainable grazing practices.

The USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Great Basin Rangelands Research Unit has a long history dating back to the 1950’s in invasive weed control and revegetation of arid environments throughout the Great Basin.

Pioneer research scientists Raymond Evans, Richard Eckert and James Young laid the foundation for range improvement practices to successfully seed desirable perennial species in arid environments as well as a better understanding of the role exotic and invasive annual grasses, such as cheatgrass, play in out-competing perennial species at the seedling stage and truncating secondary succession by providing an early maturing, fine-textured fuel that has increased the chance, rate, spread and season of wildfire throughout the Great Basin and Intermountain West. This foundation was passed on, and here we try and report on two long-term study sites of three separate precipitation zones and the important role the amount and periodicity of precipitation plays in conjunction with proper weed control practices and plant material testing to improve seeding success and decrease cheatgrass densities and associated fuels.

Bedell Flat

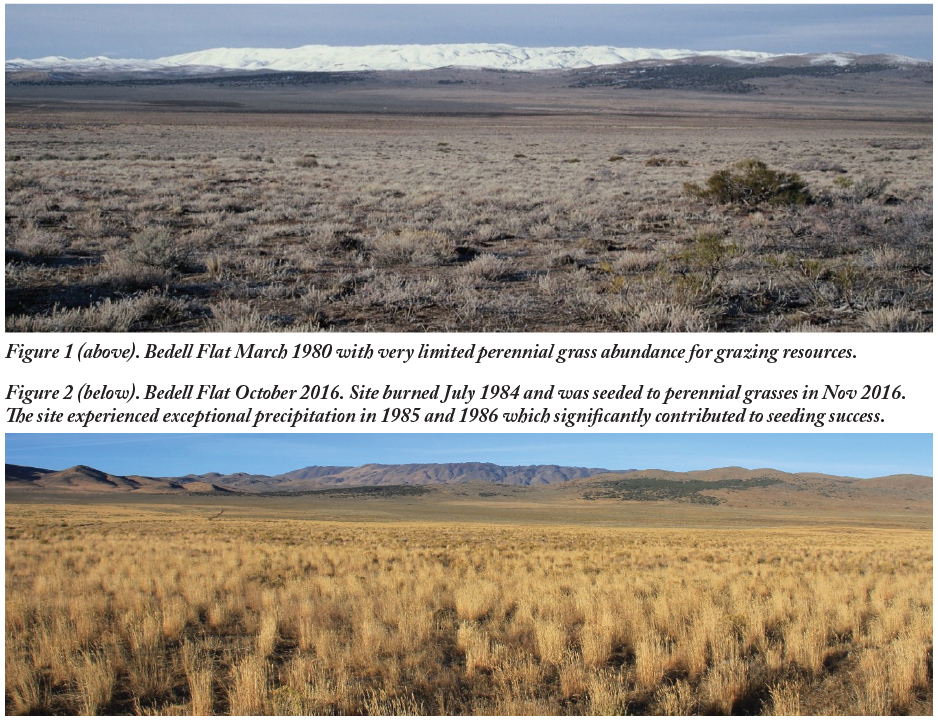

Bedell Flat, described as a 10-12” precipitation zone, consists of legacy study sites from the early 1960s. When Dr. Evans, Dr. Eckert and Dr. Young started conducting cheatgrass research in Bedell Flat. They described Bedell Flat as being in the worst ecological condition of their four cheatgrass research study sites in northern Nevada, when Dr. Evans and Dr. Eckert retired in the mid-1980s they referenced Bedell Flat as the site being in the best ecological condition of their four cheatgrass focused research study sites (Figure 1 and 2).

Bedell Flat precipitation data has been recorded regularly for more than three decades. The site is described under the Ecological Site Description (ESD) as a 10-12” precipitation zone with a fine granitic sandy well drained soil. The dominant understory species is Thurber’s needlegrass, Desert needlegrass, needle and thread grass and squirreltail with an overstory of Wyoming big sagebrush. In the three decades of collecting precipitation data (1990-1999, 2000-2009 and 2010-2019), only one decade averaged over 10” of annual precipitation, 2010-2019 which averaged 12.4” with a high of 19.8” in 2017 and a low of 5.6” in 2012. Precipitation data from 1990-1999 averaged 9.3” with a high of 13.7” in 1995 and a low of 7.1” in 1994, while 2000-2009 averaged 9.4” with a high of 16.1” in 2006 and a low of 5.2” in 2001. When looking at the ESD, 10-12” zone, amount and periodicity of precipitation is quite variable and unpredictable, such as October 2021 where the site received 5.1” of precipitation compared to October 2022 where the site received 0.04” of precipitation. This variability is common in Great Basin environments and plays a significant role in restoration/rehabilitation efforts.

In relation to successfully seeding desirable perennial species and decreasing cheatgrass densities, we have experienced near complete failures as well as high success in seeding efforts. These failures and successes are highly correlated with the amount and periodicity of precipitation in conjunction with the seeding of proper plant materials, seed mixes, seeding rates and effective weed control practices.

When looking at the amount and periodicity of precipitation it is critical to understand that average precipitation is made up of more years with less than average precipitation along with a few years where above average precipitation is received.

From 1990-1999, 70% of the time the site received less than 10” of precipitation. From 2000-2009 the site received less than 10” 60% of the time, but from 2010-2019 the site received more than 10: of annual precipitation 60% of the time. Understanding the variability of amount and periodicity of precipitation has led to plant material testing of desirable perennial grasses in an effort to suppress cheatgrass and associated fuels. Understanding that there is more of a 50% chance of less than average precipitation allows us to use plant materials that have the inherent potential to germinate, emerge and establish in 8-10” precipitation zone rather than the ESD 10-12” precipitation zone.

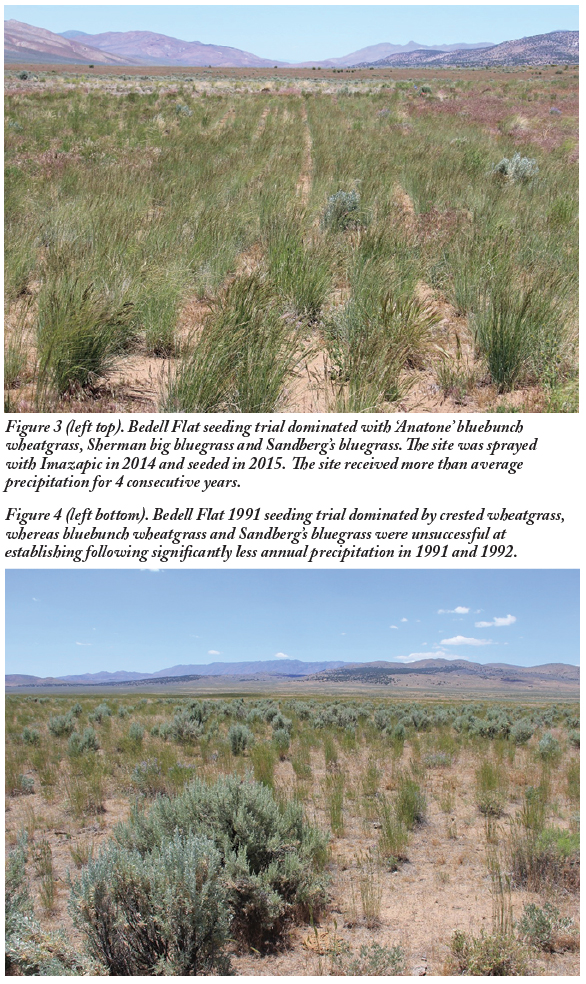

This understanding has led to the use of native and introduced perennial grasses in seed mixes in which the introduced perennial grass species have a higher potential of emergence and establishment in less favorable precipitation years while the native perennial grasses perform better on above average precipitation years (Figure 3 and 4). When testing seed mixes and seeding rates it is important to not over-load a mix with too many species as only so many plants can survive in a given area (square foot).

Effective weed control is also an important factor achieving successful seeding of desirable perennial species in arid environments. Cheatgrass seedlings are very competitive at the seedling stage with perennial seedlings, therefor it is imperative to actively control cheatgrass densities and seed banks.

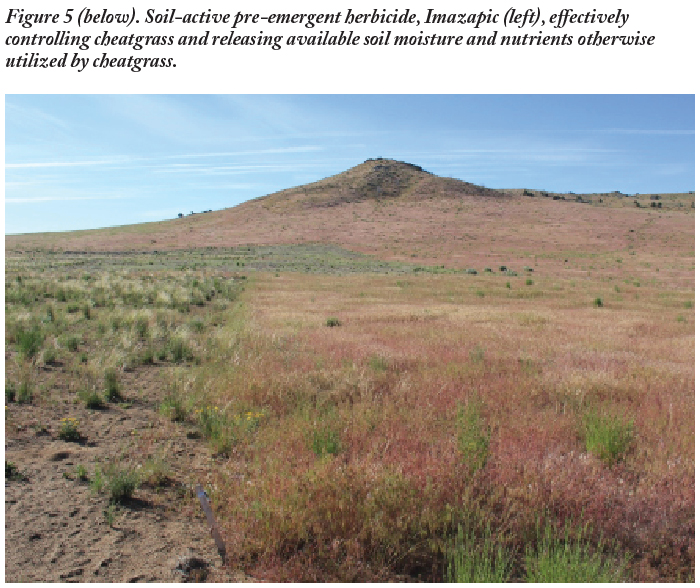

Soil-active pre-emergent herbicides are the most common method when attempting to reduce cheatgrass densities and decrease competition for seedlings of seeded species. The efficacy of the herbicide used needs to be above 95% in most cases, as it is not uncommon to have cheatgrass densities of 100 cheatgrass plants/ft², therefore, cheatgrass densities as little as 4 cheatgrass plants/ft² can outcompete our most aggressive perennial grass species at the seedling stage (Figure 5).

Figure 5 is an excellent illustration of using a soil-active pre-emergent herbicide to reduce cheatgrass competition and increase available soil moisture and nutrients. It is important to note that the sprayed plot on the left has yet to be seeded. The existing residual perennial vegetation release is evident from the reduction of cheatgrass, yet the untreated plot, right, also has residual perennial vegetation being suppressed by the presence of cheatgrass. The treated plot will have to be seeded to increase deep-rooted perennial grasses that can suppress future cheatgrass populations, otherwise the treated plot will return to the same condition as the untreated plot and be dominated by cheatgrass, which will increase the wildfire risks associated with cheatgrass.

Izzenhood

Izzenhood Basin and surrounding area is described as 8-10” precipitation zone with a fine silty loam soil. The site has repeatedly burned since the 1960s and is dominated by cheatgrass and tansy mustard. The few unburned islands that remain are dominated with an understory of Sandberg’s bluegrass, bottlebrush squirreltail and bluebunch wheatgrass. The over story is dominated by Wyoming big sagebrush.

We started testing cheatgrass control methods and plant material testing in the early 1990s in an effort to improve sustainable grazing resources, decrease wildfire threats and improve wildlife habitats, especially mule deer winter ranges.

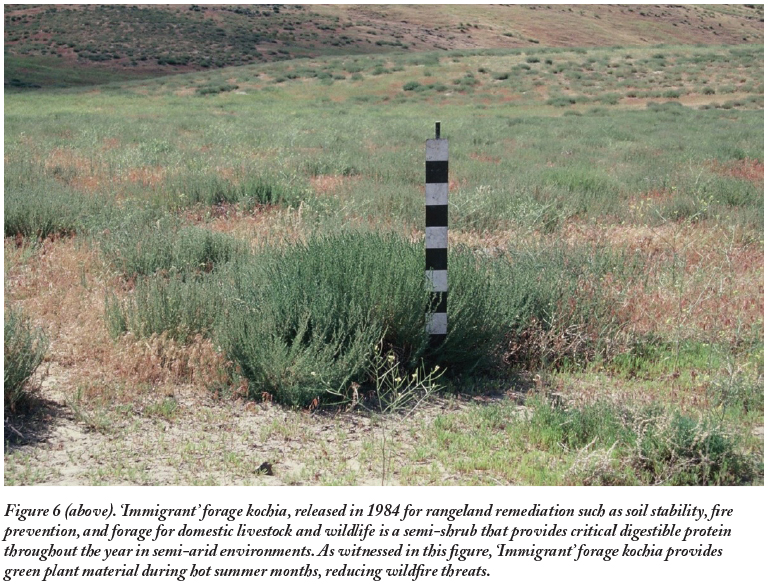

In our attempt to test plant materials, the newly released ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia was described as a semi-shrub and an excellent candidate for rehabilitation in environments common within the Intermountain West.

Perry Plummer, pioneer restoration scientist, suggested that forage kochia species provide excellent winter forage for mule deer. Looking more closely at forage kochia species revealed that ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia, the only forage kochia species released for rangeland rehabilitation efforts until the release of ‘Snowstorm’ forage kochia in 2012, does in fact provide excellent winter nutrition, resprouts after wildfire disturbance, survives heavy grazing pressure, and establishes in a wide range of soils and precipitation zone. Since ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia stays green through the hot summer months, we added this species in our plant material testing and seed mix plots (Figure 5, above).

One of the approaches we took in the 1990s (1991-1998), was to decrease cheatgrass and cheatgrass seed banks by mechanically disking the site after cheatgrass emergence and prior to seed maturity. Timing of this mechanical treatment varies by site and year, but for the most part can be achieved in late April to early May.

By disking the cheatgrass-infested habitat after emergence and prior to seed maturity, we were able to not only kill the current years cheatgrass population, but also eliminate the current years seed production, and with the action of the disks, remaining ungerminated cheatgrass in the seed bank was often buried to depths of 4” or more reducing future germination and emergence. This cheatgrass control effort resulted in 72-83% reduction in cheatgrass seed bank densities, which is not comparable to the level of control we experience with pre-emergent herbicides presently available, but for the time period was significant in making progress and reducing cheatgrass dominance.

Once the site was fallowed for the summer and seeded that fall, the germination and emergence of perennial desirable species increased with a significant reduction in cheatgrass competition. Our early approach was to incorporate greenstrip species such as crested wheatgrass, ‘Ladak’ alfalfa and ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia with native grasses and shrubs in 1,000 – 2,000 acre blocks to improve grazing resources, reduce cheatgrass and associated wildfire threats, improve wildlife resources and improve plant diversity (Figure 6).

Our research in using pre-emergent herbicides got off the ground following the catastrophic 1999 wildfire season when we started testing the pre-emergent herbicide products Sulfometuron Methyl (Oust) and Imazapic (Plateau). Initial results yielded that Oust and Plateau was reducing cheatgrass densities by 96-99%. Initial plant material testing revealed that many of the perennial grasses, shrubs and forbs were going to be very difficult to establish as limited success was experienced with the introduced perennial grass crested wheatgrass, the introduced semi-shrub ‘Immigrant’ forage kochia and the native perennial grass Sandberg’s bluegrass.

Our initial herbicide applications occurred in 1999, 2000 and 2001. Following our seeding trials in 2000, 2001 and 2002, the site received 6.7, 8.5 and 6.8” of precipitation, respectfully.

The improper application of Sulfometuron Methyl on erodible soils in southern Idaho resulted in added scrutiny of the use of herbicides on rangelands and with a short pause we re-initiated our pre-emergent herbicide research starting in 2008 with Imazapic and later with Sulfometurn Methyl-Chlorsulfuron (Landmark XP) in the Izzenhood area.

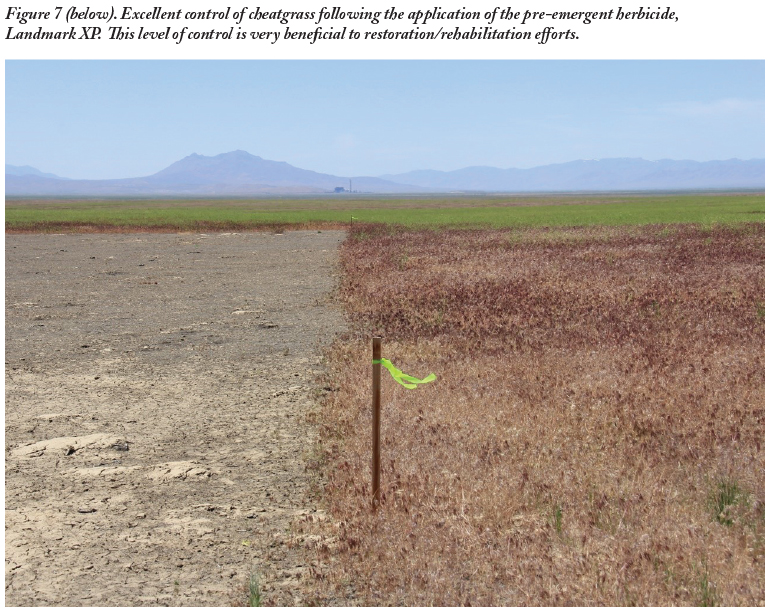

Our research yielded that Landmark XP consistently reduced cheatgrass densities by more than 98% while Imazapic efficacy was performing around 96% control of cheatgrass (Figure 7).

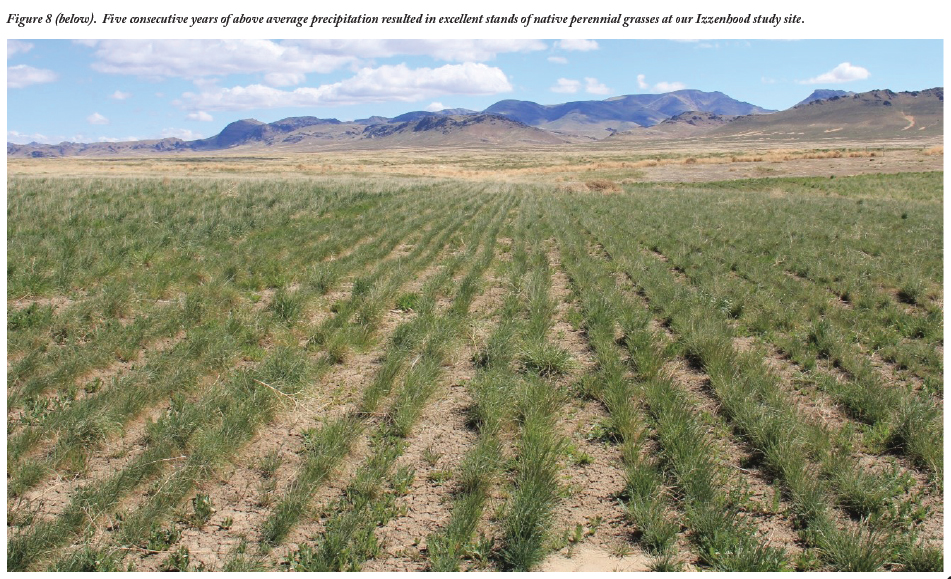

Following proper fallow of sites and plant material testing of native and introduced perennial species, we started experiencing increase seeding success with native and introduced perennial species.

The success of our seedings and perennial grass establishment is tightly correlated with favorable precipitation. Our 2008 herbicide application plots were seeded in the fall of 2009 and received 8” of annual precipitation in 2009/2010, with 5.2” occurring between October 2009 and April 2010. Other favorable years for precipitation occurred in 2015 through 2019, all above average years.

Although this 5-year span of favorable precipitation, averaging over 10”, is very rare in our experience and the success of native species was very apparent (Figure 8).

In our experience, the amount and periodicity of precipitation along with effective weed control treatments are critical in restoring or rehabilitating degraded Great Basin rangelands. Our decades of attempting weed control practices, testing a variety of native and introduced perennial grasses, shrubs and forbs as well as collecting precipitation data from the site on a regular basis has resulted in many failed attempts as well as successful attempts to establish desirable perennial vegetation and improve grazing and wildlife resources.

The continued testing of weed control treatments, newly developed plant materials, innovative seed coating, etc. are doors that should remain open and may show promise in this effort to allow researchers an opportunity to develop and disseminate new and novel techniques to assist agriculture producers to develop and implement sustainable livestock practices in the Great Basin while in concert with improving wildlife habitats.

By Charlie D. Clements, Dan N. Harmon and James A. Young