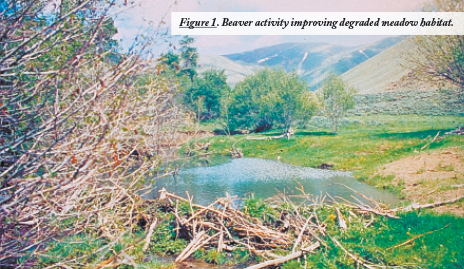

The role of beavers in riparian ecosystems of western North America is a two-edged sword. Meadows created by beaver dams and ponds, with all their associated biological diversity, bring the impressions of nature at its best (Fig. 1).

The role of beavers in riparian ecosystems of western North America is a two-edged sword. Meadows created by beaver dams and ponds, with all their associated biological diversity, bring the impressions of nature at its best (Fig. 1).

Over-utilization of woody vegetation, bank erosion, and catastrophic floods from bursting beaver dams form a contrasting view. This review of the role of beavers in past and present riparian ecosystems is offered to encourage land managers to be aware of the importance of these animals. This review concentrates on the western Great Basin, but the principles discussed apply to western North America.

Taxonomy

The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) is one of two species belonging to the rodent family Castoridae. The other species (Castor fiber), resembles the North American beaver in size and appearance, but is found in Europe and Asia. The earliest beaver fossils date from the mid-Tertiary of North America in which fossil beavers include giant forms. The modern day North American beaver dates from the Pleistocene.

Historical Relations

Much of the earliest exploration of far western North America can be attributed to the search for beavers by trappers. During the early 19th century beaver pelts, as a source of felt for hats, along with demands for fur for garments, brought trappers to the wilderness. Finan MacDonald and Michael Bourden led the 4th expedition of the Hudson Bay Company in 1823 that reached the extreme northern part of the Great Basin. Bourden was killed by Indians and MacDonald wrote, “when that country will see me again, the beaver will have gold skin”. Peter Skene Ogden then led the next six brigades for the Hudson Bay Company, and first reached the Great Basin in 1826 at the present location of Malheur Lake, in east-central Oregon. On that trip he wrote, “I may say without exaggeration, man in this country is deprived of every comfort that can tend to make existence desirable. If I can escape this year, I trust I shall not be doomed to endure another”. But Ogden did return and from 1828-1830 explored parts of the Great Basin which lie in present day Idaho, Nevada, and Oregon. The wanderings of fur trappers created tensions among the Spanish, French, English, Russians, and Americans, all of whom were attempting to establish and maintain their claims over what eventually became the western United States. These pressures led the Hudson Bay Company to develop a policy of deliberately over-trapping the eastern and southern borders of their Pacific Northwest territories. This destruction of the beaver resources was designed to discourage American trappers from encroaching on what was claimed as British territory. Trappers continually pushed on to new trapping areas because the existing beaver populations were largely destroyed by excessive trapping that failed to leave viable colonies to repopulate trapped areas.

By late in the 19th century much of the North American beaver population was over exploited. Near the end of the 19th century many states adopted protective laws concerning wildlife resources which included bans on trapping beavers. Game management agencies on the stage and federal level began reintroducing beavers to areas where they had been completely removed by trapping and to areas where they did not previously occur. Currently beavers probably exist over a broader range in North America than they did at contact time with European man.

When Peter Skene Ogden explored Nevada from 1828 to 1830, he recorded that the Humboldt River had five forks, three of which contained beavers, and that beavers were quite numerous in those forks. He also recorded beavers to be present in other systems of Nevada, such as the Colorado and Owyhee Rivers, but stated that the Carson, Truckee, and Walker Rivers were free of beaver signs. All of these mentioned systems currently contain beavers, along with many other systems which were recorded by early explorers to be free of beaver signs. Reintroduction programs probably can be credited with the present occurrence of beavers in many areas.

Were beavers actually native to those systems that were recorded to no have beavers? Considering that the main purpose of these early explorers was to find areas occupied by beavers, and they had qualified trappers along, their records of certain systems being free of beavers at the time of their passage should be very reliable. Could beavers have been native to systems like the Carson, Truckee, and Walker Rivers before early explorers passed through, and, if so, what brought about the extinction of beavers in these systems? Perhaps disease, over trapping by native Americans, or predation caused their disappearance, or maybe they were not native for some unknown reason.

Life History

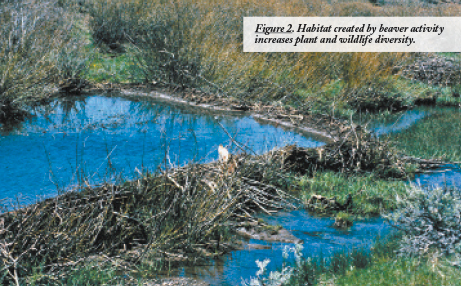

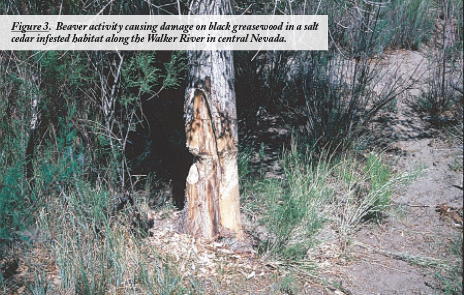

Beavers may be exceeded only by man in their abilities to alter the environment. Through their construction of dams, beavers can change degraded meadows into a pond environment with a dependent diversity of animal and plant species (Fig. 2). For example, the density and species diversity of birds has been found to increase due to beaver activities. In contrast to such desirable effects of beavers, they also can cause flooding of agricultural areas and highways and create havoc with irrigation systems. Beavers can also overutilize preferred woody species along streams, such as aspen and cottonwoods, and in so, cause a temporary decrease in tree species diversity, as well as eat themselves out of house and home (Fig. 3). A beaver colony is made up of one or more families consisting of a pair of adults, yearlings, and kits. Beavers are known to be monogamous, colonial, and territorial. If a beaver’s mate dies, a new mate is selected from dispersing two-year-olds or other unmatched adults. Beavers breed once each winter and have a gestation period of about 107 days. Litters consist of from one to nine kits. The litter size corresponds with the quality of the environment the colony occupies and the severity of the winter. The young are born with open eyes and fur and weigh about a pound. Newborn kits can move about within the lodge. At about two months of age they are weaned and must forage outside the lodge.

As yearlings, beavers learn to become accomplished builders. They leave their home lodge in search of mates and establish new lodges. They may use old dams, and/or lodge structures that already exist by refurbishing them or they may build their own structures. They start building a dam, which usually takes place from August through October, by placing branches at a chosen site and adding mud and other debris from the bottom near the dam. Once the height of the dam is near the preferred level, the construction of the lodge begins.

The building of the lodge starts with the beavers gathering and piling sticks on shore close to the water. Beavers then start piling sticks in a chosen area and keep adding until a substantial pile starts to accumulate. Mud is then added to the bottom of the pile. The chosen site may be surrounded by water, which they prefer, or they may build it along the edge of an impoundment or on shore.

Beavers are vegetarians and feed during fall and winter on the tender bark of willows, aspen, cottonwood, and alder. During spring and summer they prefer to feed on sedges, grasses, and forbs, and other aquatic and riparian plants.

Population Dynamics

Because their ponds and lodges serve as a safety refuge, beaver populations are not preyed upon intensely by native carnivores. Bobcats, coyotes, wolves, mountain lion, bears, wolverines, and lynx have been known to take beavers. Where wolves still exist, beavers may be an important component of their summer diet and predation upon beavers can be quite high. Diseases such as Tularemia and rabies may also affect beaver populations. With natural enemies not being a major factor in population control for beavers in most areas, man and his activities have a large influence on population dynamics. Harvest rates tend to reflect prices being paid for beaver pelts.

Management

Management plans for riparian areas should include an active plan for beaver management. A beaver colony will selectively exploit the woody vegetation of a riparian area. In western Nevada, along the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada, beavers will virtually eliminate black cottonwood from the riparian zone, but leave mountain alder. This changes the tree density, tree height, availability of tree cavities, and many other aspects of the riparian habitat. Conversely, unlimited trapping can eliminate the beaver population from riparian areas, which can decrease the diversity of a riparian area. Research suggests that beaver pond ecosystems can provide important habitats for nongame breeding birds in the Western United States. Habitat changes resulting from beaver activities can have extreme influences on the quality of a riparian system and can be either negative or positive. Each individual area is different and therefore management plans may need to be specific for each area. The most practical way of controlling beaver population is through systematic harvesting of surplus animals. This can prevent damage to the riparian habitat while maintaining the beaver population. In this age of awareness of animal welfare it is necessary to involve the general public in the design of management plans for beaver management. Unlimited beaver populations can be bad for riparian habitats and ultimately for beavers themselves. On the other side of the coin, to remove beavers completely from an area would eliminate the natural part of the environment that is important to many species of animals and plants. Beaver management can be very emotional with difficult issues for land managers to work with, but they are important aspects of natural resource management.

By Charlie D. Clements and Dan N. Harmon