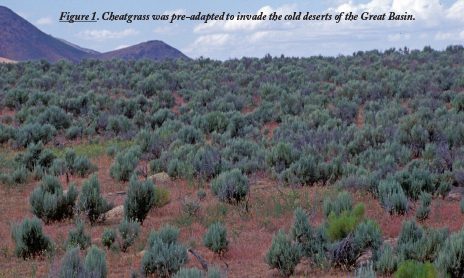

The accidental and subsequent invasion of cheatgrass throughout millions of acres of Intermountain West rangelands has resulted in rangelands formerly dominated by native shrub and grass species being converted to cheatgrass dominance. Cheatgrass is native to the cold deserts of central Asia, which are very similar to the big sagebrush/bunchgrass and salt desert shrub ranges of the Intermountain Area of North America. Cheatgrass was first collected in Pennsylvania in 1861 and believed to be accidentally introduced in contaminated wheat and then dispersed from farm to farm and across railways through equipment and stock. By 1902, cheatgrass was identified in Nevada and reported to occur along railways, roadsides and croplands. By 1935, cheatgrass was abundant throughout the Wyoming big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities throughout the Great Basin (Figure 1).

The accidental and subsequent invasion of cheatgrass throughout millions of acres of Intermountain West rangelands has resulted in rangelands formerly dominated by native shrub and grass species being converted to cheatgrass dominance. Cheatgrass is native to the cold deserts of central Asia, which are very similar to the big sagebrush/bunchgrass and salt desert shrub ranges of the Intermountain Area of North America. Cheatgrass was first collected in Pennsylvania in 1861 and believed to be accidentally introduced in contaminated wheat and then dispersed from farm to farm and across railways through equipment and stock. By 1902, cheatgrass was identified in Nevada and reported to occur along railways, roadsides and croplands. By 1935, cheatgrass was abundant throughout the Wyoming big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities throughout the Great Basin (Figure 1).

The central issue in any discussion of the ecological ramifications of cheatgrass invasion and dominance on Great Basin rangelands is the role cheatgrass plays in the stand renewal process. The stand renewal process is based on the premise that the species composition and dominance of a given community are highly influenced by how the tenure of the previous assemblage of plants on the site was terminated. Plants do not live forever, sooner or later they die, and new seedlings have to be recruited either to perpetuate the preexisting community or to introduce a new plant community to the site. For example, early researchers recognized burning as the stand renewal process for big sagebrush communities. Researchers pointed out that big sagebrush stands tend to consist of shrubs that are roughly the same age, within 10-15 years, which they concluded that the previous community on the site was catastrophically destroyed and the decade plus variation in age is a reflection of big sagebrush’s slow recolonization due to big sagebrush being killed in wildfires, no resprout ability following wildfire and limited seed dispersal. It is within the array of the stand renewal process that the current burning of Great Basin rangelands operates.

Historically, Great Basin rangelands have experienced 10 kinds of stand renewal process:

- Pre-European; A dynamic in relation to climate, the fire interval that occurred prior to European contact in the Great Basin (including aboriginal uses of wildfires).

- Vertebrate and invertebrate herbivory.

- Promiscuous/prescribed burning.

- Attempts at absolute control of wildfires on rangelands.

- Substitution of mechanical control by plowing for wildfires as a stand renewal process for big sagebrush/bunchgrass plant communities.

- Substitution of herbicide applications for wildfire for big sagebrush/bunchgrass community renewal.

- Wildfires fueled by cheatgrass.

- Grazing management introduced as a substitute for mechanical or herbicidal stand renewal in big sagebrush communities.

- Wildfires burning in native grasslands that were restored through grazing management.

- Fires burning in annual grass dominated communities.

It is through this diverse array of stand renewal processes that give light to the many successional plant communities that can occur in big sagebrush/bunchgrass potential communities in the Great Basin.

Fire Interval Before European Contact: The first stand renewal process that occurred in the Great Basin is the most difficult to identify or quantify. Estimates of the interval between wildfires in the big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities before European contact are highly variable and often controversial. Those that believe wildfire played a large role tout that wildfires were quite frequent, while those on the other end of the spectrum believe wildfires were quite infrequent and occurred rarely. Fire scars of western juniper for example suggest that wildfires in southeastern Oregon may have been as frequent at every 5 years, while others have reported western juniper fire scars in northern California as nearly a century apart. Pioneer researchers pointed out that wildfire intervals in big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities had to be at least greater than every 15 years, otherwise early explorers would have reported on the prevalence of grasslands and rabbitbrush/bunchgrass communities rather than big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities they described as they traveled west. These pioneer researchers also highly suggested that wildfire interval of big sagebrush bunchgrass communities was most likely every 60-110 years, but wildfire intervals prior to European contact remained a puzzle.

Vertebrate and Invertebrate Herbivory: Obviously, herbivory was a stand renewal process in the Great Basin prior to European contact. Some researchers report that it must not have been a major factor because the population and density of large herbivores was extremely sparse. Pronghorn antelope browse on big sagebrush at all seasons of the year, but there have been no reports of big sagebrush stands being killed by excessive pronghorn browsing. Mule deer population densities in the Great Basin were reported as very low at the time of European contact, therefor their impact on big sagebrush stand renewal had to be minimal. Bighorn sheep were most likely restricted to more rugged, mountain portions of the Great Basin where escape topography existed instead of vast landscapes of big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities. Rocky Mountain Elk, were not reported as very abundant in the eastern part of the Great Basin and were reported as absent from the western portion of the Great Basin and the American Bison had withdrawn from these regions prior to European contact as reported by early explorers and settlers. Researchers report that vertebrate herbivory was most likely confined to small mammals, with rabbits being the most numerous. Insect herbivory was a form of stand renewal in big sagebrush stands in the Great Basin before European contact and continues to play a role in these communities. An example of this is the sagebrush defoliator, a moth that in some years defoliates large blocks of big sagebrush. Severe infestations can kill large percentages of older big sagebrush plants in a community, but the younger more vigorous sagebrush plants usually recover. The resulting stand renewal occurs without the woody species giving up total dominance of the site, which happens with burning.

Promiscuous Burning: Promiscuous burning has become quite uncommon, although people still deliberately set fires. Passive and unintentional promiscuous burning caused by such agents as improperly discarding cigarettes, campfires, or fires caused by vehicle or off-road vehicle exhaust has increased significantly as human population has increased and expanded into the Great Basin. Early pioneer reporter, David Griffiths, visited the northwestern portion of the Great Basin in 1899, he reported that he saw numerous wildfires in the mountains and that they were supposedly set by sheep herders in the hope of enhancing early spring forage production for the next grazing season. Researchers may not give them credit, but sheep herders and ranchers have long known that that fire reduces competition from woody species, increase the production of nutritional herbage, and promote nutrient cycling and availability. Sagebrush was also a necessary and widely used fuel for much of the 19th and 20th centuries in the Great Basin. Cowboys, sheep herders and prospectors preferred to camp where there was widely available fuel supply, preferably pinyon, juniper or mountain mahogany, but often at the lower elevations, big sagebrush was the fuel of last resort. The disproportionate harvesting patterns can be attributed to pioneers selecting watering holes and meadows for camp sites therefor contributing to the stand renewal process for these specific sites and communities.

Absolute Control of Wildfires: The early 20th century resulted in a conservation movement in the United States that was built on a program of stamping out forest fires and putting an end to promiscuous burning. Choking smoke, followed by acres of charred and blackened landscapes along with loss of human life provided dramatic images that the American people embraced and called for conservation of natural resources. The ecological consequences of attempting to exclude fire as a stand renewal process in American forests, woodlands and rangelands were not understood for much of the 20th century. Early Forest Service Bulletins often included a photograph of an old-growth ponderosa pine tree with a pronounced fire scar accompanied by a caption noting how destructive fires were in pine woodlands. The government’s policy of excluding wildfires during the 20th century led to a greater expansion of woody vegetation in the Great Basin than had occurred since the neoglacial period some 5,000 years ago. Researchers in the mid-20th century started reporting the importance of fire as a natural part of the environment. Some of these researchers had learned about the importance of fire while they worked summers on fire suppression crews in their earlier years. The tenure of the Forest Service and the Grazing Service during the first 60 years of the 20th century coincided with the dramatic decrease in the number of acres of big sagebrush /bunchgrass rangelands burned in the Great Basin. In the case of big sagebrush communities, the reduction of wildfires was more biological than regulatory, there simply was not enough herbaceous vegetation on these shrub-dominated, over-grazed rangelands to support wildfire ignition and spread. Even cheatgrass was biologically suppressed by excessive grazing. Vast acres of big sagebrush communities, lacking an understory of perennial herbaceous vegetation, were caught in an ecological time warp as the sagebrush roots mined the inter-space between shrubs for nutrients and water, opening the door for an invasive annual which happened to be cheatgrass.

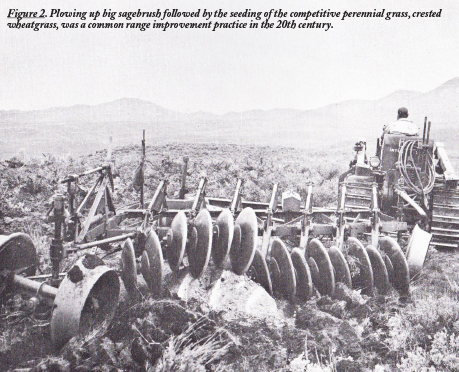

Mechanical Removal of Sagebrush: Dense big sagebrush stands were barriers to the development of irrigated farms in the early days of reclamation projects in the Intermountain Area. Homesteaders had to laboriously grub out each sagebrush plant in preparation to grow crops. Federal government, under the goal of improving productivity of western rangelands during World War II, developed mechanical equipment to plow and seed degraded big sagebrush stands. As a substitute for burning as a stand renewal process, custom built plows were constructed and pulled behind large tractors to destroy degraded big sagebrush habitats that lacked a herbaceous understory needed to carry fire (Figure 2 below). This led to more than one million acres of big sagebrush being plowed up and seeded to crested wheatgrass in a relatively short period of time. The success of these seeding tremendously enhanced the forage supply of Nevada rangelands. Estimates in the 1960s suggested that these crested wheatgrass seedings provided nearly 25% of the forage based for Nevada’s livestock industry. Increasing the forage base and using crested wheatgrass in the spring when the native perennial grasses are most susceptible to damage from grazing, reduced grazing pressure on the native perennial bunchgrasses, but it also reduced the grazing pressure on cheatgrass, which produces copious amounts of seed. Federal agencies offered seedings to grazing permittees as bait to gain acceptance for reduction in the number of permitted animals or change the season of use, which also favored cheatgrass.

Application of Herbicides: By the mid-20th century, it was proposed that the herbicide 2,4-D be used to spray big sagebrush communities in place of pre-scribed fire as a tool because public land management agencies were completely committed at the time to a policy of excluding wildfires. The herbicide experiments were careful to only spray big sagebrush communities that still contained sufficient native perennial grasses to occupy the environmental potential, otherwise cheatgrass would be the vacuum species. The stand renewal process using 2,4-D was that of either a release of native perennial grasses and improved herbaceous forage, or the advancement of cheatgrass. Sites that resulted in the release of native perennial grasses returned to big sagebrush dominance while the sites that were invaded with cheatgrass remained cheatgrass dominated ranges. The stand renewal process is relevant to the current status of cheatgrass and wildfires. It was very important to understand that sites that were planned for herbicide applications to renew big sagebrush stands would only work if the proposed site had sufficient perennial grasses to be released and occupy the site. The problem though, was that those actually applying the herbicide treatments often did not follow this guideline which opened the window to cheatgrass dominance and associated fuels and fire risks. On top of this, was the recommendation that the site be rested following the herbicide application, usually deferred from grazing for two growing seasons, therefore if native perennial grasses were not sufficiently present, cheatgrass again benefited from this management action and increasing cheatgrass dominance.

Wildfires Fueled by Cheatgrass: Intentional exclusion of wildfires from big sagebrush/bunchgrass communities by fire suppression and unintentional exclusion through removal of herbaceous fuel by excessive grazing resulted in an increase in big sagebrush stands with little to no native perennial grass understory. Wildfire was reintroduced to degraded big sagebrush communities with cheatgrass providing the fuel to spread the fire from shrub to shrub. In the late 1990s, the Nevada Section of the Wildlife Society put together a working group to develop a white paper on the Section’s “Fire Statement”. Wildlife officials were not pleased with the end product because they viewed it as pro-fire. The paper stated that fire could be beneficial in the mountain brush communities, but not beneficial in the lower big sagebrush and salt desert shrub communities. Even early researchers struggled with burning degraded big sagebrush stands that had a cheatgrass dominated understory, because big sagebrush plants in degraded communities can live for decades, succession appears to be frozen and the lack of forage perpetual. If degraded big sagebrush communities are burned, the community will convert to cheatgrass and sprouting shrubs like rabbitbrush. In years with above average precipitation, these burned areas produce a large amount of forage. Once a cheatgrass plant is established, no matter how diminutive, a seed bank is established. Even during dry years, when cheatgrass seems to disappear from the sagebrush stand, the seed bank is intact. Each year with sufficient moisture, cheatgrass enlarges its’ distribution and density in the stands until conditions are right to support a wildfire. The increase in wildfire frequency from cheatgrass fuels further supported cheatgrass dominance and re-occurring wildfires.

Grazing Management: Rest-rotation grazing management as a substitute for brush and weed control followed by artificial seeding as a stand renewal process in big sagebrush/bunchgrass plant communities has been nearly universally applied since the mid 1960’s. Several factors combined to end the golden age of range improvement, mechanical/herbicide brush control and revegetation. These included the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires environmental impact studies before range improvement projects are implemented, a growing opposition to range improvement practices from vocal environmental and wildlife professional management groups. Seeding of crested wheatgrass in particular was viewed as only benefitting the livestock industry while at the same time degrading natural communities. Range improvement projects also needed to be funded, and politicians were sensitive to adverse publicity from these groups. Rest-rotation grazing was successful in restoring the perennial grass portion of the community in the higher elevations with higher potential where remnant stands of perennial grass remained in the understory, but on a much larger scale, the lower elevations of Wyoming big sagebrush and salt desert shrub communities rest-rotation grazing ensured cheatgrass dominance. Rest-rotation grazing in these communities resulted in the accumulation of huge amounts of cheatgrass fuel during years the pasture was rested and during the period when the community received deferred grazing until after seed ripe. This was a recipe for massive wildfires, and that is exactly what occurred, therefore the stand renewal process was one of fire and further dominance of cheatgrass.

Fires Burning in Annual Grassland Communities: Repeated fires burning in cheatgrass dominated landscapes has become the most extensive stand renewal process on many landscapes. It is commonly noted by researchers and managers that wildfires in cheatgrass dominated habitats do not destroy the litter on the soil surface and that a near continuous layer of cheatgrass seed was left behind. The presence of shrubs allows the fire to burn hot enough and for a long enough period of time to kill the majority of cheatgrass on the surface and a portion of seed in the seed bank, but as can be witnessed following wildfires, cheatgrass presence can be immediate or with the second year. The abundance of cheatgrass herbage obviously influences its fuel characteristics, if the precipitation is favorable for cheatgrass growth and the site does not burn or receive appropriate grazing levels to reduce fuels, the dried carry-over herbage adds to the next years fuel load and can lead to catastrophic and extensive wildfires. Wildfires are a necessary step in the transformation from shrub steppe to annual grass dominance

Conclusion

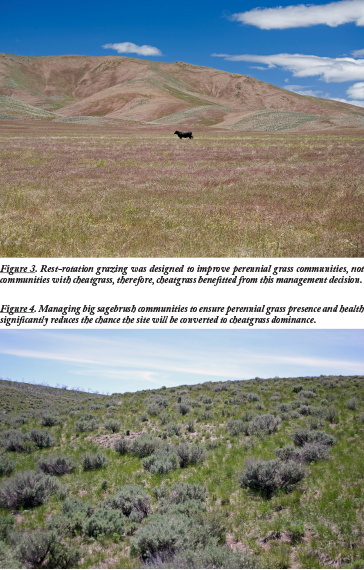

It is easy to fall into the trap of believing that all of the ecological problems associated with cheatgrass in the Great Basin would be solved if wildfires were eliminated. Cheatgrass invades a community, not because of wildfire per se, but because of the relative lack of competition from degraded populations of perennial grasses. Cheatgrass also invades high ecological condition native plant communities because there is a niche available for a competitive annual grass that native plant species do not fill. Excessive, improperly timed, and annually repeated grazing enlarges the adaptive niche available to cheatgrass. Cheatgrass dominates because of this degradation and destruction of sagebrush by wildfires. Stands that become old, decadent and dense suppress perennial grasses that are needed to suppress the exotic and invasive annual, cheatgrass. Passive management of shrub communities ensures an increase in fuel loads, increased wildfire risks and the transformation of shrub communities to cheatgrass dominance (Figure 3 below). Active management of habitats to improve perennial grass densities decreases wildfire frequencies and allows for the return of critical browse species (Figure 4 below). Fire as a stand renewal process is an inherent part of the Great Basin ecology, especially in the big sagebrush/bunchgrass zone.

By Charlie D. Clements and Dan N. Harmon